The un-spinning of Putin

New research on Russia and Belarus points up the pitfalls of the Kremlin's new approach to censorship

Vladimir Putin’s control over Russia’s media is, for all appearances, complete. His control over ordinary Russians’ minds may suffer as a result.

Since launching his full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Putin has turned a separate set of guns on Russian media, silencing all influential voices of dissent within the country, and forcing those who refuse to be silent into exile. But as I show in a new PONARS-Eurasia Policy Memo, the outcome of this assault is likely to be a loss of political leverage.

Putin’s Russia is — or, at least, was — the quintessential ‘spin dictatorship’, a system of maintaining autocratic power not through coercion and violence, but through persuasion and co-optation. As described in Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman’s influential new book, such systems have come largely to displace ‘fear dictatorships’, because they allow leaders to sustain their dominance while minimizing costs and maximizing benefits. They write:

…spin dictators manipulate information to boost their popularity with the general public and use that popularity to consolidate political control, all while pretending to be democratic, avoiding or at least camouflaging violent repression, and integrating their countries with the outside world.

Indeed, the Russian approach to media control has, for almost all of Putin’s time in power, been one of co-optation. For two decades or so, media publishers and editors have been encouraged — often forcefully, but only rarely violently — to censor themselves and their journalists.

Yes, there are some media, particularly the television stations, whose news agendas are directly dictated by the Presidential Administration. And yes, there are other media who manage to avoid state influence altogether. But much of the Russian media space has occupied a kind of grey zone, for which the guiding principle is what the leadership of RBK — installed in 2016 after the newspaper published an investigation into Putin’s daughters — called the “double yellow line”: if you cross it, you’re done. That has left a considerable grey zone, however, in which numerous influential media outlets have sought to preserve a modicum of independence.

That has never been the case in Belarus. Throughout that country’s post-Soviet history, the state has maintained direct control over broadcast media. What independent media were allowed to arise were consistently banned from covering politics. Facing felony convictions for criticizing President Alyaksandr Lukashenka, independent Belarusian media have operated very much underground.

As I wrote in a research article in Post-Soviet Affairs last year, that kind of draconian media control hasn’t served Lukashenka particularly well. As state media insisted that the country faced no threat from the Covid-19 pandemic, Belarusians increasingly turned to independent media — mostly run from overseas, accessed online through VPNs — for reliable information, much as they had learned to do on economic affairs for years. As a result, when state media trumpeted Lukashenka’s allegedly resounding electoral victory in August 2020, large numbers of Belarusians were disinclined to believe them. When that disbelief turned into a massive protest movement, Lukashenka’s tightly controlled media machine was singularly useless in his effort to restore control.

One reason why Belarusian state media proved so ineffective, I argued in that Post-Soviet Affairs article, was that patterns of Belarusian media consumption had become highly polarized. In fact, which kind of media a Belarusian tended to consume — independent vs state-controlled — was a much stronger predictor of political opinions than age, geography, social class or education.

By comparing Belarus directly to Russia, the PONARS-Eurasia memo puts that finding in even starker contrast. Drawing on a series of surveys I conducted in Russia and Belarus in 2019, 2020 and 2021, the memo has two key findings:

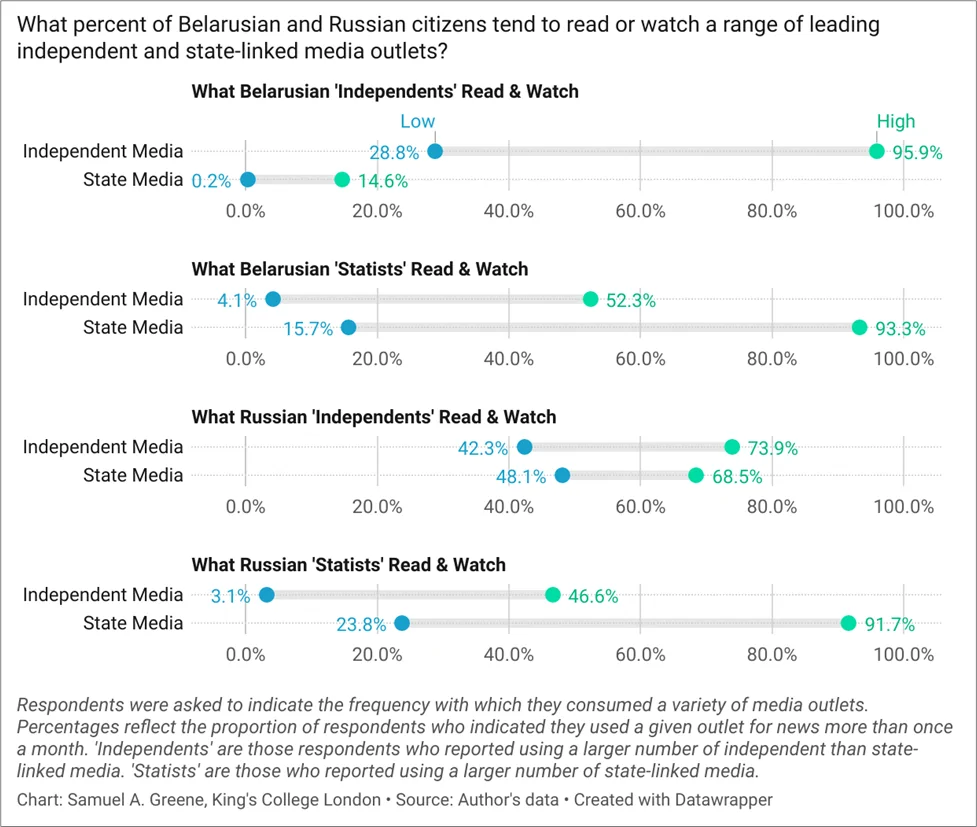

First, media audiences in Russia — at least up until 2021 — were much less polarized than in Belarus. As the figure below shows clearly, Russians on both sides of the pro/anti-regime media divide still had a lot of exposure to messaging from the other side. Belarusians, by contrast, had almost none.

Second, the extension of media control — such as the takeover of Vedomosti in Russia, or the shut-down of Tut.by in Belarus — had diametrically opposite results in the two countries. In Russia, Vedomosti retained many of its readers and even gained new ones, allowing the Kremlin to use the expansion of the ‘grey zone’ to expand its influence. In Belarus, the attack on Tut.by only drove media consumers further out of the regime’s reach.

The problem for Putin, of course, is that, having throttled Dozhd and Ekho Moskvy, having blocked access to social media and having imposed 15-year jail sentences for criticizing the war, he’s chosen to follow Lukashenka down the path of draconian media control — and thus increased polarization. This was done, of course, to increase control. The data, however, suggest that it will have the opposite effect.

To quote the memo:

Given recent developments in Russia, the Kremlin may want to take notice of Lukashenka’s struggles in the media sphere. Russia’s pre-2021 approach to media control allowed for many media outlets and perhaps most media consumers to exist in a grey zone, in which oppositional messages could not be entirely excluded but in which few oppositional citizens could be impervious to state messaging. Moscow’s current tack risks undoing that, pushing oppositional media consumers into a space beyond the state’s reach, even as audiences for state television continue to decline. As oppositional audiences grow, Putin—like Lukashenka—will find it increasingly difficult to win them back.

For further thoughts on this research and its implications, see my recent lecture at the Monterey Initiative in Russian Studies:

I am not sure that Putin's approach to media control can really be considered as "soft" or an example of "persuasion" and "cooptation" unless one wants to consider the murder of journalists, like Politkovskaya, as well as the ruthless harassment of others through sham prosecutions for "unpaid taxes" or other fabricated transgressions, to be "soft."

I think the reality is different. There isn't a real substantive difference between the approach of the two regimes. What seems different in Belarus is only so because Lukashenka had an advantage of 6-7 years. Putin arrived at a scene whose quasi-democratic and quasi-liberal features he deeply loathed but which, simply because of Russia's size and significance to the world (as well as being under much more scrutiny that Lukashenka ever was), he could not roll back immediately. But make no mistake: this isn't because of consciously pursuing different policies. Imagine if Putin had started his tenure in 1994. None of the "gray zone" would have ever been allowed to exist. In this sense, Putin is now arriving exactly where he always wanted to be and where he would have been if the 1990s, which he so detests, had never happened.