In a Facebook post marking Vladimir Putin’s 70th birthday, the Russian political commentator Sergei Medvedev recalled a column he had written exactly 10 years earlier. Then, to mark his 60th birthday, Putin famously disguised himself as a very large crane and flew with a flock of the birds in an apparent attempt to assist in their endangered migration.

Putin, Sergei wrote, was a sad little man, staging stunts of increasing absurdity in a vain effort to create a cult of personality in the absence of any discernible personality. In the ensuing period, Sergei remarked yesterday, Putin had “taken on infernal characteristics, f*cked up an entire country and is threatening to destroy the world, but at the same time the surprising thing is that he has become only more pathetic and more absurd.”

I hear what Sergei is saying, but I’m not sure I agree. It’s hard to be angry at someone who is pathetic and absurd – but it’s very hard not to be angry at Putin.

What I’m thinking about

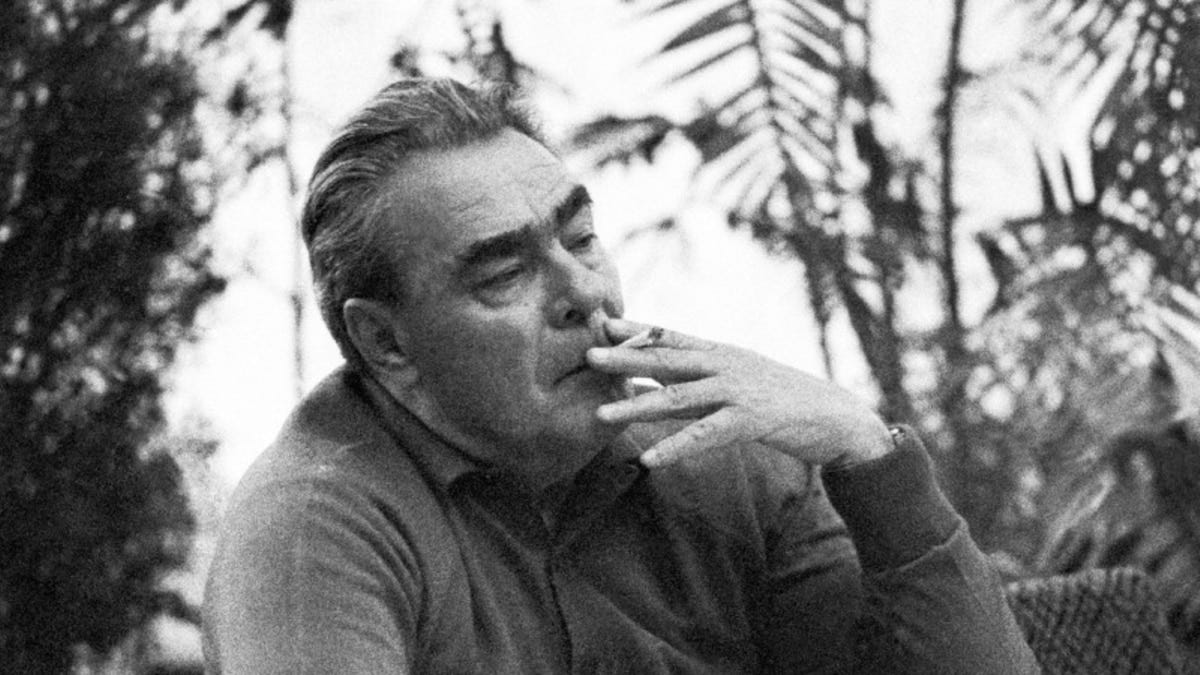

Russia needs a Brezhnev.

Hear me out.

On Friday, Graeme Robertson and I were invited to do a Twitter Spaces and podcast with Grid, tied loosely to the release of the (updated — and cheaper!) paperback edition of Putin vs. the People. The host, Josh Keating, asked us about whether elite dissatisfaction was an emerging threat to Vladimir Putin. I rambled, as usual, but Graeme hit the nail on the head:

Maybe some people listening are familiar with the movie “The Death of Stalin.” This situation has a lot of similarities to that. People who were sitting around the table with Putin, being humiliated by him on television on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine, they probably hate him as much as anybody does. But their problem is, “If we were able to take the old guy out, and that’s a big if, who do we get next? And what’s usually happened in the past is that whoever comes next then eliminates the rest of us as his potential competitors and people who know where the bodies are buried.” So, you not only have to be able to coordinate, you have to be confident that whoever replaces Putin will treat you better and not immediately turn on you. That’s the classic dynamic of these kinds of political systems.

Stalin, of course, did go — though not of his own volition — and he was followed by Nikita Khrushchev. By any rational measure, Khrushchev was a better deal for the Soviet elite and, as well as for the average Soviet citizen (though perhaps not the average Hungarian citizen): broadly speaking, people stopped disappearing and dying. But only a decade later, it wasn’t good enough: while Khrushchev tended not to remove inconvenient underlings from the face of the earth, he fairly frequently removed them from the offices that provided power and privilege. Ungrateful, they turned to Leonid Brezhnev for an alternative.

What Brezhnev offered — more to the point, what he was compelled to offer — was a different kind of Soviet governance: one that was specifically designed to serve the interests not of the leader, but of the Soviet elite as a whole. Ministers, enterprise directors, heads of institutes and functionaries of all levels — the nomenklatura entrusted with access to the levers of power — went from being expendable subjects under Stalin and Khrushchev, to being constituents under Brezhnev and his successors.

This was not, of course, an effective way of governing the country. Having shielded themselves both from top-down and bottom-up accountability, the Soviet elite had every incentive to hoard resources and very little incentive to build communism. As the political scientist Valerie Bunce wrote in 1983:

…instead of generating stability and growth, [Brezhnev’s] corporatist deal generated neither, and political bankruptcy went hand in hand with economic bankruptcy.

Members of this elite treated their departments and factories as fiefdoms, from which they could extract benefits and build networks of patronage — and that was a feature, not a bug, of the system of power over which Brezhnev presided, as the Sovietologist Robert Tucker wrote in 1981:

[Brezhnev] offered consensual leadership for order and stability. He has been content with, and may owe his longevity in power to, his willingness to be first among equals in a truly oligarchical regime….

Note the word oligarchical, used a decade and a half before we would start talking widely about Russian oligarchs in the post-Soviet period. The present, surprise surprise, has roots in the past. Russia’s post-Soviet elite — including those who emerged directly from the Soviet nomenklatura, and those who emerged to replace them — inherited a set of expectations about the purpose of power, expectations best summarized in Henry Hale’s seminal book on patronalism. They also inherited a set of expectations about the man in charge, chief among which is the expectation that he rules in their interest. This war has broken that bond — hence Josh’s question.

The problem, as Graeme and I tried to explain, is that dissatisfaction on its own isn’t enough to create political change. People need to believe, (a) that an attempt to remove the leader is possible, and (b) that whatever comes next will be better, or at least not appreciably worse. Putin, of course, maintains a security apparatus attuned to point (a), but point (b) has been at least as important when it comes to keeping him in power. Up to now, every member of Russia’s elite has been a winner in this system, even if individual fortunes have waxed and waned. Change will create winners and losers, and no one can know ahead of time who will end up in which category. The powerful incentive, then, is to sit tight.

Unless you’ve got a Brezhnev. Soviet elites dissatisfied with Khrushchev would have faced the same challenges and anxieties. And yet somehow, they settled on a candidate who would get them where they wanted to go: stability and prosperity (for the few, if not the many), but more importantly political inclusion (again, for the few, not the many).

If we wait long enough, of course, Putin will exit the scene the way Stalin did. It’s not entirely beyond the realm of possibility that he will exit the way Hosni Mubarak did. But if you’re among the many who are pinning their hopes on a palace coup, then you’re hoping for him to exit the way Khrushchev did – and that means you’re hoping for a Brezhnev.

Now, the obvious question is, how did Brezhnev come about? I don’t honestly know. Time to go back to the library. (Or, if you’re an historian of Soviet politics, enlighten us in the comments!)

What I’m reading

The journal Nations and Nationalism has a new special section out, featuring a number of essays on Russia’s war against Ukraine. All of the contributions are worth reading, but two struck me in particular and have occupied much of my mind this week.

The first is by Eleanor Knott, a political scientist at the London School of Economics and author of Kin Majorities, a comparison of structures of identity and citizenship in Moldova and Crime, which, if it isn’t already on your reading list, should be. In her piece for N&N, Eleanor argues that we shouldn’t be thinking about Russian nationalism in the traditional (and traditionally problematic) terms of ethnic vs civic nationalism – i.e., identities tied to (supposedly) primordial ethnicities (think Hitler), or to more ethnically inclusive patriotic constructs (think De Gaulle). Rather, the nationalism that Eleanor argues drove Putin to war – and which might thus seem to hold some sway among the population that complies with his war – is an “existential nationalism”, one defined not by disputes between national identities, but by disputes about the very right of a nation to exist. Moreover, the fact of Russian existential nationalism forces Ukraine into the same position. Eleanor writes,

Ukraine is fighting for the right to exist and maintain its right to determine what that existence should look like (democratic, multicultural, tolerant and multiethnic). Russia is fighting for a version of Ukrainian existence that is non-consensual and hierarchical, where Ukraine is subservient to Kremlin hegemony and ideology, where Russia decides what is good and evil, and right and wrong, and where Russia has the right to occupy whatever territory of Ukraine it chooses. Existential nationalism is Russia's motivation to pursue war, whatever the costs, and Ukraine's motivation to fight with everything it has. Of course the stakes are different: Russia is not being invaded by Ukraine. But Russia's war is existential for both Ukraine and Russia, as I argue in this piece.

A similar theme is developed by Brian Girvin, a political scientist at the University of Glasgow. The nationalism espoused by Putin, Brian writes (and I hope he’ll forgive the familiarity; unlike Eleanor, I don’t know Brian personally), explicitly divides states into two categories: those, like Russia, that are primordially legitimate and thus whose sovereignty and integrity are unquestionable; and those, like Ukraine, that are historically artificial and thus whose sovereignty and integrity are inherently subject to revision by more primordially legitimate states.

I am not sure where I stand on Brian’s core argument, which holds that the war reflects a latent tension in the global system between the borders left over from empire and colonization, which often cut through communities of identity, and the recognition of the right to self-determination – a tension that, the essay argues, can and frequently does give rise to war. To my mind, at least, that tension recedes to a large extent when the demand for self-determination is genuine, and is genuinely respected. Outside of democratic practice, there is no legitimacy to the claims for revision, or to denials of revision. But Brian’s point stands, to the extent that most such wars are fought in and/or among non-democracies.

The bigger problem Brian identifies, though, is that it isn’t just Russia sees the world in terms of legitimate and illegitimate states and borders. He writes,

This assessment brings into relief the continuing salience of nationalism for most people in most states. It also identifies the strength of state and majoritarian nationalism and the significance of imperial nationalism and irredentism in the twenty-first century. One conclusion is that political independence is much more precarious since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The post-colonial consensus that all states are equal is now seriously in doubt.

Restoring that consensus might be something worth fighting for.

What I’m listening to

As I wait impatiently for L.A. Salami’s new album to drop, I’m enjoying the album’s aptly titled single, Desperate Times, Mediocre Measures. If it’s any indication, the album will have been worth waiting for.

But if you’re like me and don’t want to wait for the rest, try The City Nowadays and Day to Day – and if that last one doesn’t tear a hole in your soul, well, I can’t help you.