TL;DRussia Weekend Roundup

27 August 2022: Radical empathy, plus texts and tunes (one last time from Durham)

It’s that time of year again: time to mark the last batch of make-up exams. That, and the smell of impending master’s dissertations, is a sure sign that summer’s coming to an end.

I’m not teaching this fall, but as you might gather from my thoughts this week, I almost wish I were. The exams I’ve read so far were a pleasure — full of engagement and creativity and understanding. And they got me thinking: if my students can figure this stuff out, maybe there’s hope for me?

What I’m thinking about

A friend and colleague of mine (who will remain anonymous) got into a bit of hot water this week for publicly suggesting that Western leaders and the experts who advise them will eventually need to think about the ways in which Western policy may have precipitated the events that eventually created the circumstances in which Vladimir Putin declared all-out war on Ukraine. That sentence is convoluted for a reason: this friend and colleague did not say that the West provoked the war, caused the war, or even made the war more likely. The argument was simply that in making the decision to go to war, Putin may have felt that he was responding to things he didn’t like in Western policy — and that if we want to avoid future wars, whether involving Russia or China or anyone else, we might want to bear that sort of thing in mind.

Now, as it happens, I don’t agree with said friend and colleague on their analysis of Putin’s thought process. As I’ve written before, my own analysis suggests that Putin went to war primarily for domestic political reasons. But it is not inherently unreasonable to argue that foreign policy — even if viewed through Putin’s distorted prism — played a role in his decision-making, and thus that he had the West in mind when deciding to go to war. My friend and colleague’s analysis is logical, empirically grounded and internally consistent.

That is to say, I can see where my friend and colleague was coming from. I can also see where my friend and colleague’s critics were coming from, however. Arguments that assign blame for this war to anyone other than Vladimir Putin have the consequence (intended or otherwise) of robbing Ukraine and Ukrainians of agency. To say that Western leaders might have prevented this war by preempting Ukraine’s fate is not much better than saying that Russia had the right to go to war for the same purpose.

Nothing, of course, could have been further from my friend and colleague’s mind — but words, once written, belong to the reader, not the writer, and most readers could not read the text the way I am convinced it was intended. My friend and colleague, in other words, was pilloried for an offense against framing.

This fact — the importance of framing — came into focus for me when I read three consecutive Substack posts by another friend and colleague, Jonathan Weiler. A political scientist writing and teaching on American politics at UNC, Jonathan declared this week ‘framing week’ and set about explaining the fallacies embedded in three popular ways of talking about US politics: the “polarization frame,” the “populism frame,” and the “fairness frame”. All three of these, Jonathan writes, are both instantly recognizable and at least partly false. Yes, American politics has less middle ground than it used to, but one party has moved more to the extreme than the other. Yes, Trump and his acolytes use populist rhetoric, but they don’t actually represent popular interests. And yes, some people will pay off more of their student loans than others, but most Americans are not morally offended by that. And yet, the frames persist.

As my first-year Sociology of Politics students know, the power of frames — and, from Jonathan’s perspective, the problem with frames — is not simply that they give us recognizable and understandable vocabularies for talking about the world: it’s that they also give us assumptions about cause and effect. They tell us why things are the way they are and they cement our expectations about the future. Thus, if we talk about the problem with American politics as one of polarization, then we’re only able to talk about it in terms of both parties, and as a result we’re unable to design a solution that addresses the reality of largely one-sided radicalization.

Jonathan’s argument is that journalists, opinion leaders and politicians (at least those of good will) need to recognize the power of frames and begin to open up new avenues of action by learning to talk about things in new ways — radicalization, say, instead of polarization, or education as a public good, rather than a private good. I agree with that, but I’d take it a step further. When a frame becomes dominant in a segment of society, it is very, very hard to dislodge, in part because you’re no longer pushing up only against logic: you’re pushing up against socialization. Telling people they need to think about things and talk about things in a new way is telling them they need to think and talk in ways that will put them out of step with their social environments. That’s one reason why my friend and colleague has found it so difficult to push through the criticism: by challenging a dominant frame, my friend and colleague has departed the realm of intellect and entered the realm of identity.

There is a solution, though — one that will also be familiar to my sociology students. Every year, in one of the first lectures in the course, I ask my students what they would think if I told them the sky was purple. Most, of course, would assume that I had either a vision problem, or a mental one. Why? Because they can see that the sky is blue (or, rather, since I teach in London, that it is grey). From that perspective, the sky is not purple, and the purpleness of the sky is a problem that extends only to me. But that’s wrong, because I’m a part of their life, the professor with the purple sky, and so my purple sky is all of a sudden a part of their reality. Imagine, then, that in addition to believing in a purple sky, I believed that the Covid vaccine carried a 5G microchip with a direct line to Bill Gates. As long as I am behaving in accordance with my understanding of the world, the 5G microchip that is not in fact embedded in my left shoulder is in fact very much part — and very much a dangerous part — of their reality.

Understanding how to deal with something like vaccine hesitancy or a pandemic of purple skies requires more than just a knowledge of epidemiology and physics: it requires us to take ourselves out of our own shoes and, however uncomfortable it may seem, to put ourselves into someone else’s. It requires us to learn how to see the world the way someone else does, to understand the assumptions of cause-and-effect that make their world go around even if we find those assumptions strange or abhorrent.

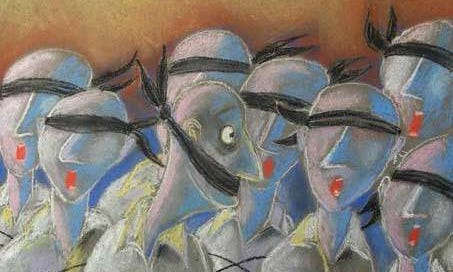

This skill — what Penn State professor Sam Richards calls “radical empathy” — is the core skill of sociology, and to my mind at least, it’s what makes sociology such a powerful discipline. Crucially, empathy is not the same thing as sympathy: practicing radical empathy does not require us to accept or condone other people’s views, or to share their emotions. It simply requires us to recognize that other people’s realities are as real to them as ours are to us. Simply, of course, is the wrong word. There is nothing simple about it. But when we put radical empathy at the core of our analytical practice — when we stand where other people stand, see what they see, know what they know — we gain much greater insights into why people behave as they do. And with those insights, we might learn how to have better conversations about the things that matter.

What I’m reading

In early September, CEPA will launch a major new report on Russia’s offensive cyber capabilities — be sure to sign up for the launch event — and as I’ve been going through Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan’s excellent text, which delves into the history of Russia’s various cyber commands and the blurred lines between legal and illegal activities, the consequences for domestic targets of repression have loomed large in my mind. I’m grateful, then, that Andrei sent me this piece (in Russian), published Thursday by the star BBC Russian Service investigative reporter Andrei Zakharov, delving into just how powerful Russia’s surveillance systems have become.

Authorities in Moscow, Zakharov writes, feed massive volumes of video data from cameras in the metro, along sidewalks and even in residential entryways through four parallel algorithms, in a system costing some $7.5 million annually — and that’s only on the municipal level. Federal authorities are likely spending orders of magnitude more. Coupled with data from social media and mobile devices, the systems have allowed Russian and Belarusian authorities to track down and detain protesters while still in the metro. A new system currently under development is designed to “determine the emotions of people walking down Moscow streets,” Zakharov writes. Smile!

Despite all that technology, though, two things are clear. One, as the Russian anthropologist Aleksandra Arkhipova has noted, most people prosecuted for political infractions in Russia aren’t caught through surveillance: they’re reported on by colleagues, neighbors and strangers. (If you read Russian and you’re interested in the human side of Russian political life, check out Aleksandra’s Telegram channel, in which she writes, among other things, about the growing tide of snitching.)

And two, neither pervasive surveillance nor ubiquitous snitching were enough to keep Daria Dugina alive. For some thoughts on the ways in which the assassination of a visible nationalist propagandist might change the complexion of the war, check out Kseniya Kirillova’s latest for CEPA. Among the initial policy reactions, she notes Maria Butina’s proposal that school children be trained to identify Ukrainian saboteurs and agents. More snitching it is, then. (For more on the implications and context of Dugina’s death, check out my conversation with The World.)

And while we’re on the topic of the nonsensical, Maxine David delves into the farce and tragedy of Tory party policy on Russia. “While there are differences between Sunak and Truss,” Maxine writes, “neither gives much cause for optimism that the UK fully understands the Russian threat or that it can help to lead in making Europe more secure.”

And here I was, longing for Britain.

What I’m listening to

This is my last weekend in Durham for a while, so I’m feeling homesick in advance — and maybe more than a little blue about the end of summer. To pick up my spirits, I’ve dived into No Rules Sandy, the brand new album from hometown heroes Sylvan Esso. It’s a great listen and far and away their most adventurous work yet, but it’s maybe not quite the right vibe to round out the summer. For that, nothing beats “Ferris Wheel”, even if it is two years old.

Thanks for the part on radical empathy, it's a good reminder not just for politics/polarization but everyday situations, e.g., at work. I can be hard to muster up the courage sometimes, but it pays off.

Hi Sam, Greetings from a former KCL colleague, just to say how much I value these blogs. Yours and Comment is Freed are an invaluable guide to Russia/Ukraine, thanks for providing.