This edition of TL;DRussia was written in transit from London to Durham, North Carolina, and thence to Washington, DC — which is a fancy way of apologizing in advance for the typos, grammatical mistakes and non-sequiturs that will inevitably follow!

As I’m en route to DC for the annual CEPA Forum conference — chairing panels, among other things, on transatlantic strategy vis-à-vis Russia and on setting benchmarks for post-Putin reform in Russia itself — I wanted to take a moment to highlight some excellent work by CEPA colleagues. Early in April, CEPA published a thought-provoking and unusually (for a think tank) heartfelt report by my Ukrainian colleague, Elena Davlikanova, on the pitfalls and booby traps facing eventual post-war Russian-Ukrainian reconciliation. And just last week, we published a paper by former US diplomat and Senate Foreign Relations Committee expert Jason Bruder on the accomplishments of Penny Pritzker as US Special Representative for Ukraine’s Economic Recovery as she completed her year in that post, and on how the US can maintain leadership on that front going forward. Both are well worth your time.

What I’m thinking about

Three things are on my mind this week, and I’m trying to figure out whether—or how— they’re related.

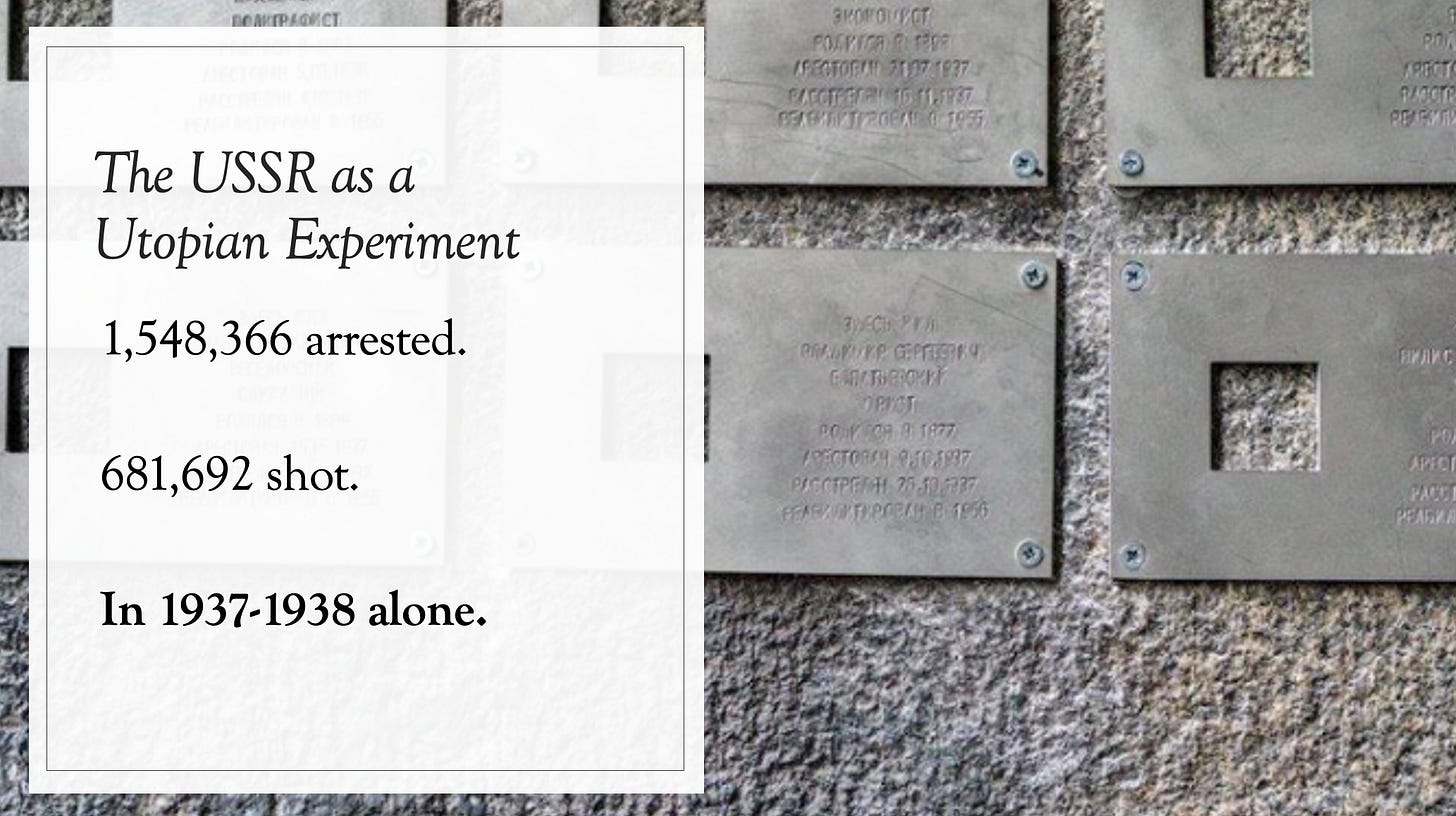

The first thing is ideology. I was giving a lecture to a group of British diplomats and civil servants on Thursday—a lecture on the rise, fall and legacy of the Soviet Union that I’ve given many times before—and found myself pausing at the slide about Stalin’s terrors. There’s not much on the slide, just numbers of arrested (about 1.5 million) and murdered (about 682,000) in 1937-8 alone. But it was the backdrop that tripped me up: a photograph of Final Address plaques on the wall of a Moscow apartment building, commemorating individual victims of Soviet totalitarianism.

Again, it was far from the first time I’ve shown this slide. I paused on it a few years ago, when the Final Address plaques—installed mostly in the 2000s and 2010s by a grassroots movement of Russians dedicated to not letting history’s lessons fade—started disappearing from buildings across the country. But I paused this time as I described to the audience what the plaques contained: the name and profession of the victim, their date of birth, and the dates they were arrested, killed and rehabilitated. I found myself wondering out loud whether the next generation of plaques would have to include another line: the date the rehabilitation was overturned. As I mentioned last week, Russian authorities have launched a large-scale campaign to revisit Gorbachev- and Yeltsin-era court decisions annulling Stalin-era repressive verdicts. I read on the train Thursday morning that this campaign had already re-convicted more than 4,000 murdered Soviet citizens, mostly accused of treason.

But there’s more. Also last week, Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed a decree identifying 47 countries and territories “implementing policies that impose destructive neoliberal ideological constructs, counter to the Russia’s traditional moral-spiritual values.” Alongside the US and the UK (and all of the EU minus Hungary and Slovakia) are such imposing powers as the Bahamas and Micronesia. Citizens of these 47 parts of the world will now have the right to seek political refuge in Russia. And while Mishustin was squaring that away, his assistant and former Chechen Prime Minister Muslim Khuchiev proposed banning the teaching of “Darwin’s theory” in schools, which, he argued, “is the first step to the moral degradation of children.” The prominent Russian Orthodox benefactor Konstantin Malofeev seconded the proposal.

The Mishustin-Khuchiev show is, to my mind, the farce that accompanies the de-rehabilitation tragedy. As serious as the revision of history genuinely is, most of the engagement with ideology by Russia’s ruling elite remains deeply absurd. Neither the designation of “destructive neoliberal” superpowers nor the targeting of the teaching of evolution will have much in the way of real-world impact. They’re useful talking points for politicians and they keep ideology front and center in the public conversation (which is real enough), but they don’t contribute to the kind of deep political and social reorganization that we associate with totalitarianism. In a word, this is not the stuff of which terror is built.

The second thing on my mind this week is marital bliss—or, actually, the rather emphatic absence thereof. Not my own, mind you, but that of one Tatiana Bakalchuk, CEO and primary shareholder of the online marketplace Wildberries and the 22nd richest person in Russia, with a fortune, at least on paper, of about $7.4 billion. In case you missed it, Ms Bakalchuk’s husband, Vladislav, is unhappy with the way she’s running the company (of which he is also a shareholder)—so much so that he (allegedly) sent an armed group to its central Moscow headquarters to shoot their way into the c-suite, leading to the death of at least two people. (For the full story, see Kommersant’s report on Wednesday.)

On one level, the Wildberries story is a dispute over shareholder rights—except that most shareholder disputes don’t erupt into gunfire. Even in the 1990s and early 2000s, when “corporate raiding” in Russia emphasized the “raiding” more than the “corporate”, it was rare to see something of quite this magnitude. Yes, people were killed in corporate disputes, but not at one of the country’s largest privately owned corporations. And anyway, wasn’t this kind of thing supposed to be consigned to history?

What strikes me about the Wildberries story is its parallels with last summer’s Wagner mutiny. Three parallels in particular come to the fore:

First, at its core, the dispute between Wagner boss Evgeny Prigozhin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu was an economic one, about who gets to profit from one of Russia’s most important enterprises—the war in Ukraine.

Second, everyone knew this was coming, just as everyone could see the growing conflict between Prigozhin and Shoigu. In both cases, of course, it seemed hard to beleive that it would come to armed conflict, but the grounds for conflict and the mounting tensions were plain to see.

Third—and most importantly—the system could not provide a way of resolving the dispute peacefully. In a rule-of-law environment, or even in a reasonably well-institutionalized authoritarian system, courts and the bureaucracy should have been able to sort these kinds of things out. In an increasingly personalized autocracy like Putin’s Russia, the role of steering powerful people away from destructive conflict falls to the sovereign, and in both cases the sovereign was asleep at the wheel.

And that brings me to the third thing on my mind this week: public opinion. A few interesting datapoints popped up in recent days. One is the release of a joint survey by Chronicles and Extreme Scan suggesting that 49 percent of Russians would be prepared to support the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, up from 39 percent last October. Some 63 percent, according to the survey would like to see a peace agreement with mutual compromises reached within the next 12 months. Now, I don’t want to overstate the meaning of these numbers. For one thing, I don’t have the full report of the survey or the underlying data, so I can’t evaluate the methodology or reliability. For another, asking people whether they would support something if the government did it is different from asking people what they want the government to do, and polls have consistently shown throughout the full-scale invasion that people express support more or less for whatever the government does, but are highly reluctant proactively to suggest a course of action other than the one currently being pursued. In other words, keep your salt shaker handy.

But a shift is a shift, and this is a shift well outside the margin of error. Assuming the underlying sampling strategy has been consistent, this is evidence of some fatigue, and it’s worth noting—and waiting to see whether it continues.

In the same ‘wait and see’ category is some new data from the Levada Center on consumer sentiment, which appears to be coming down from its (rather spectacular) peak.

Again, grains of salt here: Levada’s consumer sentiment index (like consumer sentiment indices around the world) is volatile, and we have seen much larger declines even after February 2022 with no real political or social consequence. Nonetheless, Levada’s analysis suggests interestingly that the downturn in sentiment is driven less by how people feel about their past or current economic fortunes, and more about what they expect to happen in the future.

And that, in turn, sent me further into Levada’s data, where I noticed something I hadn’t seen before. For decades now, Levada has asked survey respondents a series of questions about their opinion of Russia’s political leadership (comprising the Power Index), how Russia is doing as a whole (comprising the Russia Index), how their family is doing (the Family Index), and what they think about the future (the Expectations Index). Throughout most Levada’s polling history, the relationships between these indices have been fairly chaotic, with some going up and others going down, or moving at different rates. Take a look at the chart below, though, and in particular at the periods from March 2008 to April 2010, and then from March 2022 through to the present day.

In both of these periods—corresponding with the start of Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, respectively—the Family, Russia and Expectations Indices are in almost perfect lock step (while the Power Index soars above, more or less unrelated to the other three indices). I don’t have a perfect answer for why this is happening, but I have a hypothesis, which is this: in moments of confusion and uncertainty, Russian citizens (and perhaps not only Russian citizens) find it difficult to differentiate between their personal (or family) welfare, the welfare of the country as a whole, and their expectations of the future. In part, this may be people seeking safety in numbers. But I think it’s also a response to de-institutionalization—the same deinstitutionalization that is at the core of the Wildberries story, and the Prigozhin story before that. When the relationship between your material welfare and the welfare of the country as a whole is unstructured and fundamentally unpredictable, moments of chaos and confusion cause all of these concepts to collapse in on one another.

What does this mean? Two things, in my mind, at least. First, it means that, rather from being in a period of a euphoric rally ‘round the flag, Russia may in fact be in a period of deep confusion. Note that we don’t see the lock-step indices in early 2014, when Crimea is annexed and a real rally ‘round the flag takes off. At that point, Putin’s ratings soared, as did the Family and Russia Indices, but the Expectations Index remained volatile. This is different. Rallies like what we saw post-Crimea, as Graeme Robertson and I have shown, create a sense of euphoric but genuinely felt togetherness. This togetherness appears more forced and defensive, but it also contains a risk for the regime. Back in 2014 (and really up through 2018), euphoric togetherness allowed sentiment about Russia and personal wellbeing to remain high even when people were pessimistic about the future. Now, with the indices moving together, a drop in optimist can bring the whole edifice down. (On the other hand, strength in the other indices can buoy optimism. Again, grains of salt all around.)

Second — and this is what ties all three strands together, I think — the system is doing nothing to help people through all of this confusion. Institutions are not helping people resolve conflicts and protect their interests, with catastrophic and often violent results, as we see in Wildberries. And ideology, rather than telling people how to behave in uncertain times, is manifesting itself predominantly in wild and impotent flights of fancy. I would expect, then, the confusion to continue, and indeed to feed on itself in a vicious circle. I’m not predicting the imminent downfall of the regime or anything — you know me better than that — but effective regimes are not generally in the business of sowing confusion.

What I’m reading

A short-ish reading list this week, I’m afraid:

While we’re on the subject of confusion, that’s the primary emotion that comes across from Olga Allenova’s report in Saturday’s edition of Kommersant on Russian citizens displaced by Ukraine’s incursion into Kursk oblast. The Russian government is doing the bare minimum but doesn’t appear to have a plan to do much more than that, with the result that the displaced people (I hesitate to call them refugees) seem mostly resigned to being forgotten.

Earlier in the week, Mediazona and the BBC Russian Service published their latest tabulation of Russian fatalities, now in excess of 70,000 confirmed, and more likely 120,000 in actuality. Among other things, they note the increasing preponderance of volunteers—as opposed to mobilized fighters and prisoners—among the dead, as well as the increasing average age of the deceased. The data, however, show a downward trend in the casualty rate overall, which is somewhat at odds with what we are hearing about Russia’s willingness to sacrifice masses of men for incremental territorial gains on in eastern Ukraine. I don’t know if that’s because the reports are wrong, or the Mediazona/BBC data haven’t caught up yet, but it’s something to track.

On Friday, Novaia Gazeta’s European edition ran a thought-provoking interview with Ilya Shumanov, director of Transparency International-Russia, on the Wildberries story, which Shumanov sees as just the latest step in a long process of the return of violence and lawlessness to Russia’s political economy.

Also on Friday, Novaia Gazeta’s Russian edition ran a very long read by Alexei Tarasov on the return of forced labor as a favorite tool of the Russian penal system, and the sometimes dangerous incentives it creates for political prisoners looking to avoid traditional incarceration.

Finally, UCLA political scientist Dan Treisman has an excellent essay in The National Interest on how the slow-walking of military aid to Ukraine, far from de-escalating the conflict, is leaving Kyiv with little choice other than to pursue ever more aggressive means of defending itself.

What I’m listening to

There are, I think, different kinds of great music. There’s music that excites you from the first bar, music that stuns the senses. And then there’s music that passes over you like a slow rain, seeping in almost imperceptibly, until you suddenly realize that everything’s just a little bit greener, a little bit more lush, a little bit more alive.

That’s H.C. McEntire. Her latest album—like her previous solo work post-Mount Moriah—Every Acre, dropped something like a year and a half ago and struck me as lovely. But it’s worked its way into my bloodstream, for reasons I can’t explain and don’t really need explaining. The whole album is worth a slow, repeated listen, but I’ll leave you with this aching haiku of a ballad.

Thanks for another insightful - and beautifully written (writing while traveling seems not to have diminished your prowess) - post. Your discussion of the Prigozhin/Wildberries similarities in concert with the Levada survey data presented ideas I've not seen expressed anywhere else. Three insights in particular stand out:

* [T]the system could not provide a way of resolving the dispute peacefully. In a rule-of-law environment, or even in a reasonably well-institutionalized authoritarian system, courts and the bureaucracy should have been able to sort these kinds of things out."

**"When the relationship between your material welfare and the welfare of the country as a whole is unstructured and fundamentally unpredictable, moments of chaos and confusion cause all of these concepts to collapse in on one another."

***[T]he system is doing nothing to help people through all of this confusion. Institutions are not helping people resolve conflicts and protect their interests, with catastrophic and often violent results, as we see in Wildberries. And ideology, rather than telling people how to behave in uncertain times, is manifesting itself predominantly in wild and impotent flights of fancy."

I feel as though I should print these and post them on my refrigerator! It strikes me that we in America are evincing a good bit of undermining of the rule of law, intentional sowing of confusion, and increasingly unserious policy solutions ourselves!

I get the sense of a wider and fundamental policy objective to impose a (self-serving ) ideology on Russian life. You are picking up on selected aspects (as I did). However, I read Julian Waller’s research piece on the Russian education system. This introduces top down reforms in the education system, from infant school to university. This includes re-writing world history consistent with the Leaders view point and consistent with his aims. This I find particularly infuriating as it is about the systematic mind forming of young people to corrupt their values and knowledge base. These being the fundamental starting blocks of one’s personal framework, moral, political and informed. So my Russian counter parts neither get the opportunity to read Orwell or Darwin or understand WW2 properly for example. Cynical manipulation. Will it take? I have some doubts and that gives me hope.