The Containment Redux

Is it time to return to a beleaguered idea?

Perhaps as early as this weekend, the US House of Representatives is poised to vote—and most likely pass—a large supplemental appropriation of aid to Ukraine. This, of course, comes many months too late. The damage that Republican obstruction has done to Ukraine’s war effort may not be undoable. And yet I am grateful that House Speaker Mike Johnson appears finally to have recognized that failing to support Ukraine now will cost America immeasurably more in blood and treasure down the road.

“I really do believe the intel and the briefings that we’ve gotten,” Johnson said. “I think that Vladimir Putin would continue to march through Europe if he were allowed.”

Johnson, in other words, has joined the containment camp—and not a moment too soon.

What is containment?

If, like me, you haven’t taken enough classes in the history of international relations, containment may not mean what you think it does. As foreign policy ideas go, containment gets a bad rap, and not without reason. A strategy that was initially meant to prevent conflict between the US and the USSR from escalating into a global conflagration ended up drawing the US into myriad overt and covert wars in the name of ‘containing’ communism.

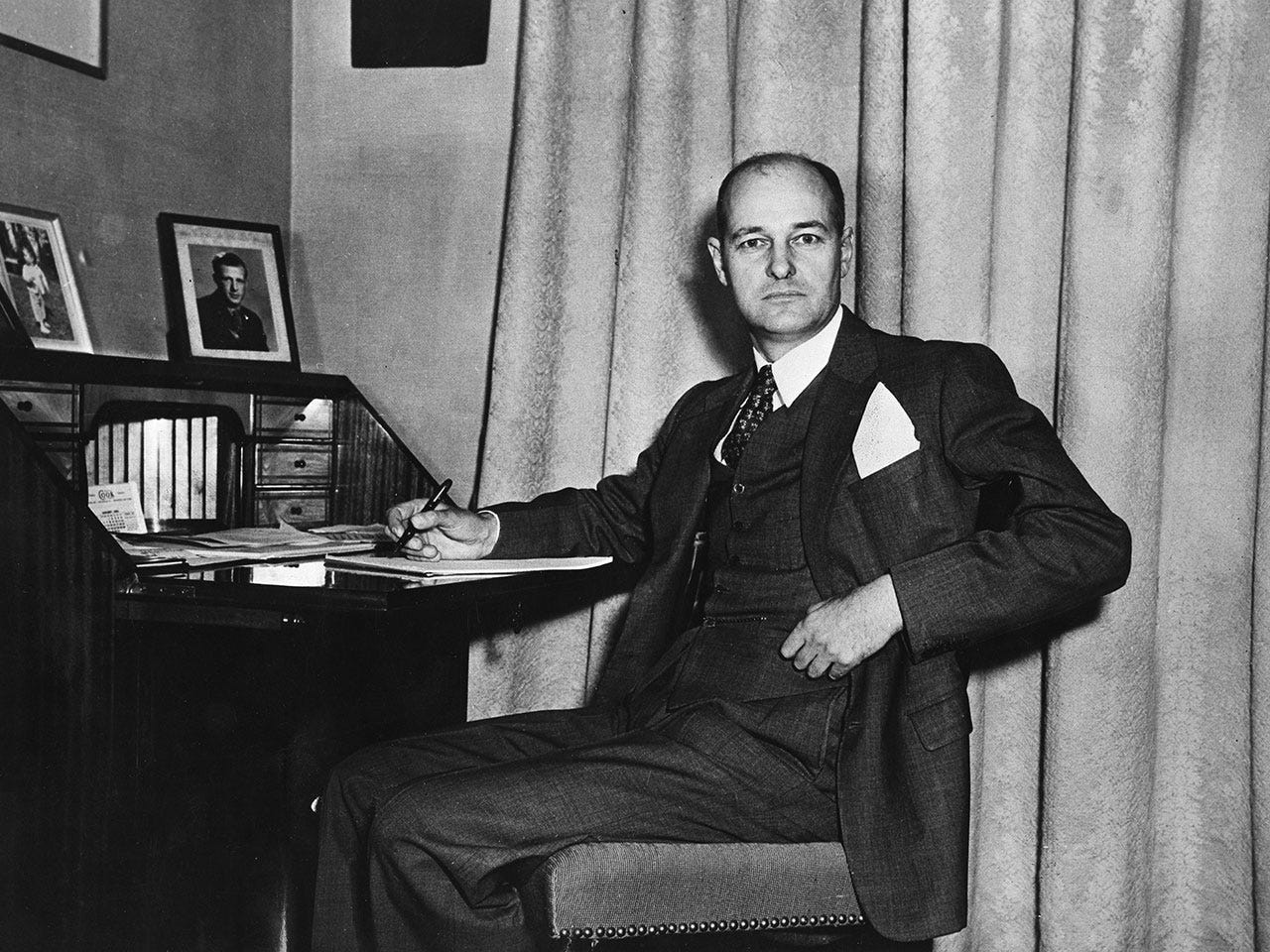

In fact, the idea of containment grew not out of the hubris of intended American hegemony, but out of humility. In his famous and influential 1946 ‘long telegram’, the American diplomat and Russia expert George Kennan wrote that the Soviet Union was committed to a view of the world that could not see the US as anything but hostile, and as such believed that it could defend its own interests only by actively seeking to undermine the interests of the United States. The US, he argued, could neither persuade the Soviet leadership to see the world differently, nor defeat the Soviet Union militarily. Faced with an adversary that could be neither persuaded nor beaten, and with whom war would be a global catastrophe, Kennan argued that the only option for Washington was to seek to prevent the conflict from spiraling out of control—in other words, to contain it.

A growing number of American foreign policy analysts have been coming to the conclusion that we now face a similar adversary, and that, as before, containment is the only available policy. Eugene Rumer and Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace made that argument in the Wall Street Journal in November. Liana Fix, of the Council on Foreign Relations, and Catholic University professor Michael Kimmage made a similar case in Foreign Affairs the same month. Together with a group of Russian, Ukrainian, European and American fellows, I added my own voice to that argument in January, as editor and penholder of a major report on containment for the Center for European Policy Analysis. And in February, ten Washington thinktanks from across the political spectrum came together on Capitol Hill to argue that now is the time to get started.

Exactly how containment should be achieved remains a subject of debate. Some analysts push for an aggressive approach, ramping up the challenge to Russia along multiple fronts in order to exhaust its resources, stretch its capacity and prevent it from pursuing a provocative agenda around the world. This would not be my preferred approach, although it’s noteworthy that the Kremlin’s vision of containing the US, as outlined in a policy document leaked to the Washington Post, hinges precisely on exhausting America’s resources, stretching its capacity and preventing it from impeding Russia’s ambitions.

In the CEPA report, we take a somewhat softer approach, built on four pillars:

Winning the war in Ukraine, because “deterrence cannot be restored until and unless Russia is defeated in Ukraine, prevented from undertaking further aggression against its neighbor, and forced to reckon with the costs of its aggression”;

Reestablishing deterrence by denial in Europe, i.e. restoring Europe’s defense capacity, such that Russia is “prevented from concluding in the context of any future conflict that time is on its hands”;

Hardening the West’s soft targets, through “an investment in the kind of world in which we want to live”, including closing off avenues of kleptocratic and malign foreign influence and recommitting to effective diplomacy, trade, investment and conflict resolution around the world; and

Challenging Russia’s hegemony in the post-Soviet space, by giving societies and economies around the region options to engage productively with the US and Europe and ensuring that EU enlargement to include Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, but also the Western Balkans, becomes a reality.

Why containment?

I’ll admit, when I first started grappling with the project that became the CEPA report, I was skeptical that containment was a fruitful idea. To me, it was too closely associated with the dangerous and ultimately destructive ideas of “domino theory” and smacked too heavily of the overly simplistic proposition that we are in a “new Cold War.” And to be honest, both of those objections still give me pause.

But the CEPA project turned me into a containment convert.

We began the project with an attempt to understand, in broad terms, how we got here. Without seeking to minimize the role of ideology and imperialism, we argued that Russia’s decision to go to war in Ukraine—first in 2014, and then in 2022—was the result of a long political evolution through which Putin and his ruling elite came to believe that it was in Russia’s vital interest to exercise political, economic and military dominance in the post-Soviet space. As their attempts at domination faced resistance, including from the West, they also came to believe that it was in Russia’s vital interest to undermine the structures of Western power, whether the soft power that made Europe so attractive to Ukrainian citizens that they would throw off Viktor Yanukovych in 2014, or the institutional power that underpins sanctions and other coordinated responses to Russian aggression. A commitment to conflict with the West that was decades in the making, we argued, would likely take decades to unmake.

From there, we pursued an exercise—involving contributions from a number of Russian colleagues who are not named as authors on the report, due to CEPA’s designation as an “undesirable organization” and thus the potential for them to be prosecuted—in thinking about Russia’s future. To be clear, we weren’t seeking to predict Russia’s future. I have never been a fan of scenario analyses and did not want to go down that road. But it is nonetheless useful to think about the factors out of which Russia’s future will be constructed, including whether and how Vladimir Putin eventually leaves office, and dynamics of elite, mass and federal politics. By looking at these factors, we sought not to determine what kind of future for Russia was probable, but to elaborate the range of futures that seemed plausible.

We wrote:

Understanding what is and is not plausible requires rephrasing the questions. First, we need to understand the degree to which political forces — whether elites or masses — are likely carry this war forward in the absence of the man who started it. And second, we need to understand the degree to which the current system of power is sustainable in the absence of war. If we can answer those two questions, then we can form reasonable judgments about the future not just of Russia’s war in Ukraine, but of Russia’s broader conflict with the West.

A large part of the ensuing analysis focused on Russia’s elite. Building on work by Ivan Fomin, we noted that the war has contributed to a restructuring of Russia’s political and economic elite into two broad camps:

The Bears, “who believe that long-term geopolitical confrontation with the West works in their favor”; and

The Foxes, “who believe that they would be better off with a return to something resembling the status quo ante.”

Either of these groups—or a coalition of the two—could plausibly end up running the country in the future. If the Bears take charge, continued outright confrontation is likely. If the Foxes win out, or if there is a coalition, some attempt at détente is possible. Nevertheless, we argued, Western policymakers should be wary of any thaw in international relations that is not accompanied by genuine democratization at home. The political evolution that led to war, after all, was an authoritarian evolution, and failure to break down that authoritarianism would likely lead us right back here.

Thus, we concluded:

Much as the Soviet Union’s sense of the world stemmed from the nature of Soviet Communism, with its ideology of inevitable conflict and its drive to undermine capitalism, so too is contemporary Russian foreign policy rooted in the nature of a system of political power that is epitomized by Vladimir Putin, but that is also overwhelmingly likely to outlast him. And so, just as the emergence of Cold War containment meant the abandonment of the dream of universalism after World War II, so too does the reemergence of 21st-century containment now mark the abandonment of post-Cold War dreams of universalism and the end of history. It is a recognition of both the hard realities of the world we inhabit, and of the limitations of American and allied power in that world.

Containment does not mean the elimination of conflict or even the basis for conflict, but only the prevention of conflict from escalating to levels that might lead to a wider war.108 Just as the object of Cold War containment was neither to defeat nor dismantle the USSR, the strategy proposed here aims neither to defeat nor dismantle Russia. Rather, the aim is to protect American and allied security by preventing the further destabilization of international relations and creating circumstances in which Moscow reliably finds it in its interests to pursue peace rather than war.

Containment begins at home

This, I think, is what Speaker Johnson has in mind when he says that he has become convinced that Russia will roll further into Europe if it is not stopped in Ukraine. Pushing back against many in his own party, Dan Coats, former Director of National Intelligence and ex-Senator from Indiana, made the same point recently in the New York Times: “The choice is America first or something else first,” he wrote. “America is always first. The real question, in this complicated and uncertain world, is what course of action will most likely serve our core national interests — security and economic prosperity.”

Contrast that with Ohio Senator and MAGA star J.D. Vance, who took up valuable space in the same newspaper counting the costs of victory, while entirely ignoring the costs of defeat. “The White House has said time and again that it can’t negotiate with President Vladimir Putin of Russia,” Vance wrote. “This is absurd. The Biden administration has no viable plan for the Ukrainians to win this war. The sooner Americans confront this truth, the sooner we can fix this mess and broker for peace.”

Donald Trump Jr., however, rather gave the game away when he tried to back Vance up:

The reality of the 21st-Century vintage of America First is that it’s not an isolationist ideology: it’s a transactionalist ploy. Trump and his acolytes are not seeking peace in Ukraine: if they were, they would have to reckon with the same truths that persuaded Johnson. Instead, they are seeking deals from which they can benefit—politically, financially, or otherwise. It’s not ‘America First’ so much as ‘what’s in it for me’.

Winning the argument for containment, then, will require not just convincing Americans and their elected representatives that Russia’s challenge extends well beyond Ukraine. It requires reconnecting American foreign policy and domestic policy, such that Americans come to see what’s good for the world as being good for them. And for that to happen, the obverse must also become true: Americans must see that their government’s solidarity abroad does not come at the cost of solidarity at home.

Towards the end of his long telegram, Kennan wrote:

Much depends on health and vigor of our own society. World communism is like malignant parasite which feeds only on diseased tissue. This is point at which domestic and foreign policies meets Every courageous and incisive measure to solve internal problems of our own society, to improve self-confidence, discipline, morale and community spirit of our own people, is a diplomatic victory over Moscow worth a thousand diplomatic notes and joint communiqués. If we cannot abandon fatalism and indifference in face of deficiencies of our own society, Moscow will profit--Moscow cannot help profiting by them in its foreign policies.1

I was reminded of this when I was reading Stephen Kotkin’s recent essay in Foreign Affairs. While the piece is an attempt to map out scenarios for Russia’s future—again, not my favorite exercise, but still very thoughtful and worth reading—Stephen comes around to an implicit endorsement of containment (although he doesn’t use the word). And he, too, notes the importance of the home front:

The government and philanthropists should redirect significant higher education funding to community colleges that meet or exceed performance metrics. States should launch an ambitious rollout of vocational schools and training.… Beyond human capital, the United States needs to spark a housing construction boom.… The country also needs to institute national service for young people, perhaps with an intergenerational component, to rekindle broad civic consciousness and a sense of everyone being in this together.

Investing in people and housing and rediscovering a civic spirit on the scale that characterized the astonishing mobilizations of the Cold War around science and national projects would not alone guarantee equal opportunity at home. But such policies would be a vital start, a return to the tried-and-true formula that built U.S. national power in conjunction with American international leadership. The United States could once again be synonymous with opportunity abroad and at home, acquire more friends, and grow ever more capable of meeting whatever future Russia emerges.

That used to be an agenda both Republicans and Democrats could get behind. If the conflict with Russia is to be contained, it must become so again.

What I’m reading

I’ve already thrown quite a bit at you, but there are a few things out there that caught my eye since last I wrote, and which may be of interest to others.

Two takes on the state of the war, both from the International Institute of Strategic Studies:

The more recent of the two is an essay in Survival by Nigel Gould-Davies, who explains what I’ve been wanting to say for a long time more cogently than I could have said it myself: “The balance of resources favours the West: its economic superiority over Russia is much greater than during the Cold War. But the balance of resolve favours Russia.”

The second, dating from February but which I only found recently, is an IISS policy memo by Franz-Stefan Gady and Michael Kofman on how Ukraine can win a war of attrition. They wrote, “The most effective way for Ukraine to rebuild its advantage is to mount an effective defence in depth, which will reduce Ukraine’s losses and ammunition requirements.” It’s wonkish, but it’s a particularly good antidote to Vance’s sophistry.

Jeremy Morris, a social anthropologist of Russia and one of the few Western scholars still able to conduct meaningful qualitative research, published an extensive and thoughtful blog post on Russia’s presidential elections and what we have learned about the nature of authoritarianism—both in Russia and more broadly. It’s well worth reading, probably twice. Morris, as I do, focuses in on “the social life of authoritarianism” which, he argues, may outweigh the cognitive factors of authoritarianism. In other words, people seem to relate their way into compliance and subordination, rather than thinking their way into it.

The Russian sociologist Asya Tsaturyan published a short paper in Socius visualizing a large and intriguing dataset on the relationship between anti-Ukraine rhetoric and anti-LGBT+ rhetoric in Russia. Intriguingly, she argues that we should see homophobia in Russia as part of a nationalist agenda, rather than as part of a conservative one. (That may be true of other countries, too.)

A significant section of my social media feeds was captured recently by discussions of a recent academic article (alas, in Russian only) by the sociologist Vadim Volkov on the concept of “irreversibility”. The piece is not an empirical one, but you don’t have to read too far between the lines to see how it applies to Russia, Putin and the war. Volkov’s theoretical innovation is to see “irreversibility” not in its classical sense as the point in a process after which the status quo ante is irretrievable, but as a social phenomenon in which people perceive an earlier version of reality as having disappeared and been replaced by a new one. I’m not sure yet what I make of the article myself, but if you’re in search of a rabbit hole (and you’re comfortable with a combination of academic Russian and sociological jargon), this may just be what you’re looking for.

As is common in diplomatic cables of that era, the word “the’ was dropped from the text.

Thank you for the excellent column. But how do we get to those 4 points in the CEPA report, especially the first two? There doesn't seem to be enough collective resolve in the US or EU for reaching those goals, even after 2 years of war in Ukraine. I haven't yet read the full report, so perhaps this is answered there, but it's hard to see how to make progress on these fronts at the moment.

A first rate article with abundant resources for further reading and reflection. Thank you.