Note to readers: First and foremost, apologies for being a day late with this week’s newsletter. Life intervened. Second, further apologies in advance for next weekend, when the newsletter will take a brief break for Thanksgiving (barring unforeseen events necessitating a rapid response).

The shifting of the ice seems to be the theme of this week’s newsletter, from nuclear-adjacent escalation, to engaging with Russia on gas, to intriguing patterns in Russian public opinion (which occupy the core of my thoughts below). Or maybe its slippery slopes.

Either way, things are feeling particularly treacherous at the moment. Be careful out there.

What I’m thinking about

Are Russians ready for peace?

My short answer is, I don’t know. My slightly longer answer is, no one else knows, either. And the slightly longer than that answer is that we won’t really know whether Russians are ready for peace until peace breaks out, or at least until it tries to. Please bear that in mind as you read. But the numbers we’re seeing point to questions, the answers to which will likely shape the Kremlin’s ability both to continue this war, and to end it.

At the end of last week, Russian Field published the results of a nationally representative survey, conducted 6-12 November, the headline of which was that a record proportion of respondents now say they would prefer that the Kremlin negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine rather than keep fighting. As I wrote in late October, when Chronicles published similar data, which themselves echoed findings from the Levada Center, there is a big difference between preferring something and demanding it. And that’s take-away number one: whatever else these surveys might be showing, they’re giving us no evidence whatsoever that Russian citizens are prepared to try to force peace on their government.

That said, there are some interesting things going on in the Russian Field numbers, which have helped clarify my thinking about what may be going on right now—emphasize may—in Russian public opinion, such as it is.

Let’s start with the headline figure: 53 percent of respondents told Russian Field that Russia should negotiate, versus 36 percent who thought it should keep fighting. That’s the highest result for ‘negotiate’, and the lowest result for ‘fight’, since the begining of the full-scale invasion, and the increase from the June survey round is larger than the margin of error.

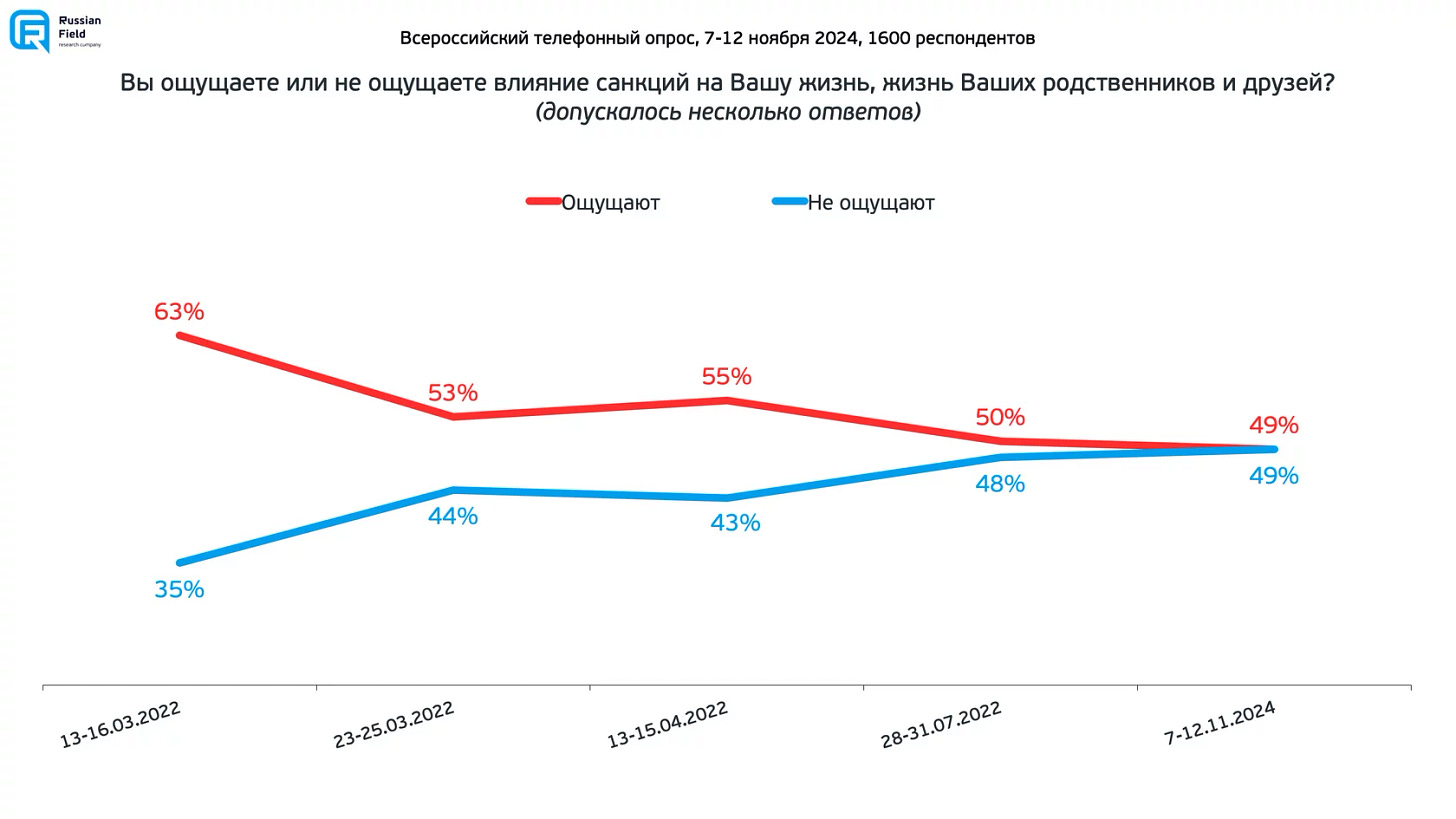

Despite the size and duration of the shift, though, the headline figure itself doesn’t tell us much about what might be causing it. We do know, however, what’s not causing it. The same survey showed that the percentage of respondents who said that feel the effects of sanctions has dropped from 63 percent when the war began to 49 percent now, while the percentage who say they have not been affected by sanctions grew in the same period from 35 percent to 49 percent (as well). So, even as inflation continues to run hot and the economy struggles to meet consumer demand, most Russian seem fairly bullish.

What about the war itself, though? Here, too, Russian Field’s respondents are bullish. Some 63 percent of respondents said they think the war is going well, versus 23 percent who think it’s going poorly. While those numbers are a bit off their June peaks, it is still a yawning gap.

The more important thing about this number, however, is what happens when you break it down by various social categories: nothing at all. Gender and wealth have more or less no correlation with respondents’ expressed opinions about the course of the war, while age is correlated only weakly.

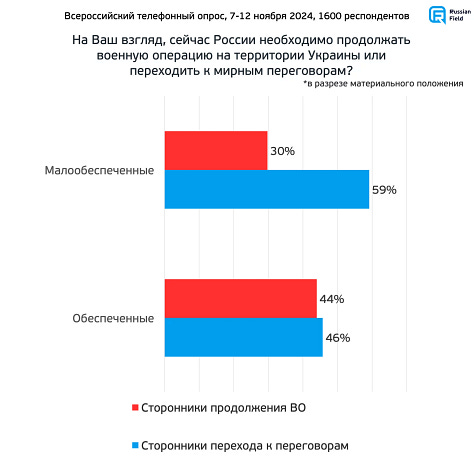

Contrast that with the breakdown on responses for the talking vs fighting question: Among men, 45 percent say they’d prefer negotiations, while 43 percent would prefer to keep fighting. Among women, however, 59 percent support talks, while only 31 percent support continuing the war. The same is true of wealth: the talk/fight split among the rich is 46 to 44 percent, but it’s 59 to 30 percent among the poor. And while respondents over the age of 45 were evenly split between talking and fighting, only 17 percent of respondents aged 18-29 and 29 percent of those aged 30-44 said they wanted the fighting to continue, versus 68 percent and 58 percent who would prefer negotiations, respectively.

What’s going on here? And why am I throwing all these numbers at you?

As regular readers of this newsletter will have heard me say before, we should not take numbers in opinion polls as though they were unproblematically representative of people’s real opinions. To do so would be to assume not just that people tell the truth when asked about their opinion by pollsters, but that they actually have opinions on the questions asked. To make matters even more complicated, in a highly politically charged environment—like wartime Russia (but also like election-time America)—the formation and communication of opinions at such is a social process. People don’t tend to form their opinions alone, after all. Opinions are formed in conversation and debate, and they serve (among other things) to help us situate ourselves in our social circles, to communicate our trustworthiness (and ascertain the trustworthiness of others), to win the dinner party, and so on. They are almost never formed and only very infrequently expressed in the highly artificial one-on-one-conversation-with-a-stranger-holding-a-clipboard setting of an opinion poll. So there’s that.

That doesn’t mean, however, that polls are pointless. If we understand responses for what they are—partial reflections of how respondents’ read the social landscape in which they exist—we can gain a valuable window into the power dynamics of the conversations the Russian state is having with its citizens, and that Russian citizens are having with one another.

Let me explain what I mean. We know that Russian society is, like most societies, stratified, and that stratification finds its way into tastes, preferences and opinions. Orientations towards popular culture, forms of leisure, travel destinations, sex and lots and lots of other things—in fact, probably most things—vary greatly by age, gender, social class, geography, and so on. However, when we see that those differences disappear, as they do in the Russian Field question about how the war is going, we can infer that there is something making those differences disappear, and that that something is power.

In this setting, power can come from one of two directions: it can operate vertically, with the state imposing uniformity on the ways people form and express opinions, or it can operate horizontally, with peer pressure and the fear of ostracism doing the dirty work. I have long argued—and continue to believe—that most of the dirty work in this regard in Russia is done horizontally. Despite the increasing ferocity of government repression, people still appear to be much more concerned about being hit on the head by their friends (metaphorically speaking, mostly) than by the authorities. Even that horizontal power, however, is shaped and enabled by the power of the state, which sets the agenda and delegitimizes dissent.

What’s noteworthy in these survey results, then, is not (or not simply) the fact of the gradual shift in expressed opinion on how the war might end, but the stark difference in the role of power in shaping that issue, compared to broader sentiment on the war. Put simply, there is clearly a greater diversity of conversations about the future of the war than there is about the war’s present (and past), and that diversity is feeding into an ability and a willingness on the part of Russian citizens to countenance and express opinions that may not have been available to them just a few months ago.

On one level, it’s not surprising that power dynamics are less present in conversations on the future of the war: Putin himself has said almost nothing on the subject. Or rather, Putin himself has said almost nothing intelligible on the subject. On Russia’s war aims and his means of attaining them, he has left himself the widest possible berth, allowing him to spin virtually any outcome as a victory. And on what Russia looks like after the war, he has said even less. Much as Putin might like to remove the future from Russia’s political discourse, however, human imaginations don’t operate that way, and his failure to provide a vision may eventually become a vulnerability.

Whether that eventual vulnerability may be materializing in the numbers we’re seeing now from Russian Field and others depends on the answers to questions we don’t have. Beyond the gender, age and wealth split, what is driving the diversity of grassroots visions of the end of the war? Is it simply fatigue, or is there a note of anxiety, too? If it’s anxiety, is it material, existential, or both? What is the relationship, if any, between Russians’ experiences of the war, and their preferences for its outcome?

We don’t have the data to answer these questions, but the Kremlin will likely be seeking them, because they hold at least part of the key to what happens next. If there is an emotional dynamic driving significant portions of the Russian public to oppose—even if passively—the continuation of the war, the Kremlin may worry that even talking about negotiations could open the emotional floodgates, after which public opinion would punish Putin if he cannot deliver or pivots back to fighting. If, however, there are material considerations at work, continuing the fight could begin to exacerbate splits in Russian society, complicating both governance and the war effort. And those are just two of many possible implications.

It also stands to reason that if Russians are divided as to the end of the war, they’re equally divided—and dividable—about what happens after the fighting stops. Indeed, it is on this front where the calcification of Russia’s political system is most visible. A more confident regime would likely address that challenge head on, devising and delivering a vision, even if only an illusory one, designed to enthrall the majority of Russians and marginalize the rest. This regime, however, remains unwilling to take that risk, with the likely result that he will continue the war for as long as he can, simply to prevent its subjects from peering over the horizon. Despite its outward popularity, its evisceration of the opposition and its geopolitical bluster, Putin’s Kremlin fears the future.

What I’m reading

Sticking with the theme of shifting ice (or slippery slopes, take your pick), much of the commentariat was transfixed this past week by Ukraine’s first use of Western long-range weapons against canonical Russian territory, Russia’s simultaneous update to its nuclear doctrine, and its subsequent use of a nuclear-capable inter-continental ballistic missile. Beyond a Tuesday Twitter thought, to the extent that the moves by all sides seemed calculated to send a message without provoking an escalatory spiral, I don’t have much of my own to say on the subject. Others, however, have had more substantive contributions worth noting:

Meduza published an extremely handy line-by-line comparison of the new 2024 nuclear doctrine and the 2020 text it superseded. In a nutshell, as reported elsewhere, the primary effect is to make it more difficult for adversaries to calculate the circumstances in which Russia might go nuclear.

My KCL colleague Ruth Deyermond had a much longer and much more substantive Twitter thread on Friday putting Russia’s activities in perspective and explaining, from a specialist’s point of view, why nothing has happened that should be seen as significantly shifting the threat needle.

Levada Center sociologist Alexei Levinson published a piece in Gorby, the upshot of which is that the Russian public is broadly convinced that a Russian nuclear strike on Ukraine would lead not to the end of the war, but to its expansion.

Putting all of this in perspective, the American Journal of Political Science published on Saturday a paper by University of Pennsylvania political scientist Hohyun Yoon, involving a quantitative analysis of threats issued by world leaders over a fifty-year period following the end of World War II. Threats, he finds, are more likely to be effective if the leaders who make them are performatively angry. Where threats are issued in calm terms, by contrast, adversaries tend not to see them as credible.

And one more on the shifting ice/slippery slope docket: On Thursday, the Wall Street Journal reported that Miami-based financier Stephen Lynch is seeking US backing for a bid to buy the bankrupt Nordstream Pipeline. I don’t know whether his idea is to try to profit from the eventual reestablishment of gas trade between Russia and Europe, or to use the pipeline as leverage with Berlin and Brussels; there are few other good reasons to buy the thing. Either way, however, it’s a colossal mistake, even the discussion of which gives succor to Putin and ulcers to America’s European allies.

And two quick parting shots on other fronts:

On Tuesday, iStories published a long-read by Irina Dolinina and Polina Uzhvak on Russia’s 20th Motorized Rifle Division, which has suffered more than 1,000 desertions. The fate of the division and the deserters is a fascinating microcosm of Russia’s war.

On Saturday, Novaya Gazeta Europe published a piece by Denis Morokhin on how the US decision to sanction Gazprombank—and the immediate ruble crash it provoked—will affect the Russian economy as a whole.

What I’m listening to

This one—a tune I first heard ages ago, from the London-based roots band Oi Va Voi—has been in my head for weeks. Looking at the state of our world today, it’s small wonder why. Politics aside, though, it is achingly beautiful.

Russia is always open for a solution which leaves Ukraine unable to join the West. And only such a solution will do. It may mean continuing a hot war, a frozen conflict, a cease-fire, a truce or even a peace accord - but only if Ukraine remains out of EU/NATO.

Russia will choose the best of the above options based on how it fares in the battlefield and subsequent negotiations, but it won't let Ukraine go away.

Perhaps Olaf Scholz has already called Miami-based financier Stephen Lynch to partner up on the Nordstream pipeline...

Thanks for your analysis, as always. Would love to hear your thoughts about Putin's increasing reliance on foreign mercenaries/troops following the news this weekend that Yemeni soldiers are now joining the fight. I can imagine a somewhat endless supply of global potential manpower he could draw from if it means he can avoid or postpone implementing conscription in Russia.