.שנה טובה ומתוקה

What I’m thinking about

Is Russia a lost cause?

I had the opportunity this past week to attend a panel discussion at one of the Washington think tanks with four Russian oppositional figures of varying age, profile and outlook. (I am leaving out names, because there is no written record to cite, and the names are in any case unimportant here.) The speakers laid out a range of visions for what might happen whenever Putin finally leaves office. Not surprisingly, all of them saw regime change as a necessary but insufficient condition for the eventual transformation of Russia into a democratic country, at peace with itself and its neighbors. More than that, they agreed that Russia’s military defeat and/or capitulation was the key to making that kind of transition possible. And they all called on Western governments to hold the feet of any post-Putin Russian regime to the fire until genuine progress has been consolidated.

None of them felt, however, that there was anything they could do now to make Putin’s downfall more likely, or alter the course of the war. At most, one of them argued, they could help Western governments devise policies that might lead to elite division and thus undermine Putin’s power—though there is precious little evidence thus far that Western policy is capable of having such an effect. Short of that, they might be able to provide guidance on how not to make things worse. But in the story they told, which is indistinguishable from 98% of what I’ve heard from exiled Russian activists since this war began, genuine agency doesn’t precede or cause regime change: it follows it. (I’ll come back to the other 2% in a moment.)

Seen charitably, the mission of the Russian democratic and anti-war movement in exile is three-fold. First, they can (and do) mobilize support from the new Russian diaspora for Ukrainian refugees and help coordinate work with activists on the ground in Russia to help find and rescue Ukrainian prisoners and children. Second, they can (and do) mobilize support to help Russian activists escape as and when they face prosecution. And third, they can (and do) work to devise policies for a post-Putin Russia, including political and economic reform, lustration and (sometimes) decolonization.

Seen somewhat less charitably, the mission of exiled Russian opposition groups, civil society organizations and media is simply to survive. And seen considerably less charitably, the mission is just to obtain funding.

Many Ukrainian organizations and activists—who are quite literally struggling to survive, while also supporting refugees, rescuing prisoners, and trying to keep their country free—are inclined to the less charitable interpretation precisely because of what they see as the Russian activists’ abdication of agency. We are fighting, they say; why aren’t you? We fought to overcome autocracy; why didn’t you? Because we have fought and won in the past, we know we are strong; are you?

After the discussion, one of my Ukrainian colleagues said the Russian oppositionists—for all their fine words—seemed morally bankrupt. While the Russians accepted passive moral responsibility for the war and the crimes Russia was perpetrating in Ukraine, they were not prepared to accept active moral responsibility for bringing it to an end. Why are so many Russian activists content to confine their responsibility to the past and their agency to the future, when Ukrainians are dying in the present?

It is possible, and perhaps tempting, to seek answers to this question in the realm of morality, to argue that Russian society is deficient in some fundamental and likely irrevocable way. As a social scientist, it is equally tempting to dismiss this argument out of hand: we are interested in analytical judgments, not normative ones. I think, however, that we ought to resist both temptations. To excise morality from our analysis is to renounce our own humanity, agency and responsibility. But to reify morality as a thing-in-itself is to renounce analytical practice as such: moral or immoral behavior has causes, just as anything else does, and we should not rest until we know them.

Now, I’m not here to say that I know the causes of this Russian abdication of agency, though I have some ideas. Part of it, I think, lies in a closer examination of Ivan Ermakoff’s work on contingency, which he develops in his study of the “collective abdication” of power in Vichy France. Seen from that perspective, Russian activists’ actual powerlessness is generated less by actual coercion, than by the activists’ shared conviction that the battle is already lost.

Another part of it, however, might lie in a re-examination of the work of the economist and social theorist Albert Hirschman. If readers know Hirschman at all, they will most likely know his work on “exit, voice and loyalty”. First promulgated in 1972, this theory describes how people—whether consumers or citizens—behave when they face disappointment. I tend to explain it to students in terms of ketchup. Let’s say you’re partial to Heinz ketchup, as I am. If the Heinz company decides to change the recipe, and I don’t like it, I have three choices:

I can exit, switching to another brand—assuming that another ketchup brand is available at roughly the same price, and that I like it better than the reformulated Heinz ketchup;

I can exercise voice, writing to the Heinz company to complain and demand they bring the old recipe back—which is only likely to be effective if lots of other people do the same thing; or

I can fall back on loyalty, continuing to buy Heinz ketchup even though I don’t like it, because I have an emotional attachment to the brand.

In most circumstances, there is a clear tradeoff between these three choices. Obviously, loyalty is what the Heinz company is counting on, allowing them to keep making profits while individuals make do with sub-par ketchup. Exit likely solves the individual’s sub-par ketchup problem at least to a degree, but at a cost, because finding a new brand you like better takes time and money. The bigger cost of exit, though, is that it detracts from voice: the more people switch brands, the fewer people are left to complain. Voice, meanwhile, is both costly (time and money, again) and uncertain: you end up eating sub-par ketchup until enough letters stack up at Heinz HQ, which may never happen. But voice has the best chance of forcing Heinz to see the error of its ways, and it reinforces a sense of powerful solidarity among ketchup aficionados. (Remember New Coke?) Of course, if enough people switch brands, then exit, too, can force Heinz to go back to the old recipe, and then everybody’s happy again.

This is, of course, about a lot more than ketchup, as Hirschman showed in a 1993 essay when he applied the theory to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Throughout most of the post-war period, East German leaders managed opportunities for exit in order to reduce demand for voice, effectively using controlled emigration as a pressure-release valve. Up through 1988, this broadly worked, helping to keep a lid on public dissatisfaction. In 1989, though, everything changed. Hirschman wrote:

The normal pattern is as follows: when customers take their business away from a firm or members desert a political party, the managers of these organizations soon become aware of declining sales or other evidence that something is wrong; they then search for the reasons and take steps to repair whatever lapses are responsible for the customers’ or members’ evident unhappiness. In the case of the GDR, this straightforward feedback mechanism worked very poorly, because the managers of the GDR had inured themselves to it … and were in general an insensitive and inflexible bunch. But the mass exodus did sufficiently impress, depress, and alert some of the more loyal citizens, those who had no thought of exiting, so that they finally decided to speak out.

Fast forward to Russia in 2022-3, and it feels like we’re miles away from East Germany in 1989. Keeping the exit option open has effectively undermined voice, by robbing the Russian opposition movements of leaders and activists, and allowing those unhappy with sanctions or the military draft to try their luck elsewhere. Despite the fact that Russian leaders are, like their East Germany predecessors, “an insensitive and inflexible bunch”, there is as yet no evidence that the exodus of as many as 1.5 million Russians has had any impact on “more loyal citizens”.

That still leaves us without an answer to two key questions: Why are the vast majority of ordinary Russians unperturbed by this show of dissatisfaction? And why are even those who are demonstrably dissatisfied so averse to their own agency?

In 1982—a decade after publishing the initial theory of exit, voice and loyalty, and a decade before applying it to East Germany—Hirschman wrote another essay, titled “Shifting Involvements: Private Interest and Public Involvement”. In it, he grappled with the question of how people decide whether to seek solutions to the sources of their dissatisfaction in the private realm or the public one. In the most basic version of the “exit, voice and loyalty” conception, this is largely down to rational choice: people will usually opt for whichever solution is the most efficient route to better ketchup. In truth, however, it’s a lot more complex. Emotion plays a part (see loyalty), as does one’s social environment: If all your friends eat Heinz, you’re not going to serve them Hunt’s. But in “Shifting Involvements”, Hirschman explored a deeper and more troubling phenomenon. People’s interpretation of both the source of their dissatisfaction and the appropriate venue to find a solution is, among other things, ideological. He wrote:

Western societies appear to be condemned to long periods of privatization during which they live through an impoverishing ‘atrophy of public meanings,’ followed by spasmodic outbursts of ‘publicness’ that are hardly likely to be constructive.

The default position for most Western societies, Hirschman argued (in 1982!), is increasingly the belief that individual solutions to problems are always more effective and appropriate than collective ones. If anything, this belief is reinforced whenever we witness an explosion of pent-up dissatisfaction, such as the populist uprisings of recent years.

This same belief is dominant in Russia. As my research has explored going back to the mid-2000s (here, here, here and here, but also see work by Jeremy Morris), virtually the entirety of the late- and post-Soviet Russian experience has been one of disconnection from the state and from the public, during which people of all walks of life and political stripes have come to see private involvements as more effective and safer than public ones. Russia, like much of the West, is stuck in this state of ‘atrophy of public meanings’, as Hirschman put it.

In part as a result, even if people’s hearts cry out for resistance, people’s heads may lead them to individualized acts of resistance, rather than public ones. The agency to which Russian citizens tend to cling first is agency over their own lives, rather than agency over the system that makes their lives miserable. It would be unfair and demonstrably untrue to say that Russian activists do not seek to achieve public aims: they do. But few of them seem to believe that much is achievable in the public realm.

It doesn’t help that the vast majority of Russian opposition activists and intellectuals are avowedly Thatcherite, arguing for classical liberalism and a heavily circumscribed state—and that brings me back to the 2% I mentioned earlier. It is no accident that active, collective resistance comes from three corners: from the left, from feminists, and from nationalists (who make up the bulk of the partisan groups mobilized by Ilya Ponomarev). All three groups are deeply rooted in an ideology that ascribes tremendous meaning to the public, as the only venue in which the existing power structure can be undone. It is also no accident that Ukrainians have built their own agency through a history of national liberation, a movement that similarly privileges the public space.

Again, I’m not claiming to have the answers here, but I do think that we’ll find them in a deeper exploration of how Russians think about the public space. If we find the answers, will they absolve anyone of moral responsibility? No. But if we don’t find the answers, we condemn efforts at change to futility. Where’s the morality in that?

What I’m reading

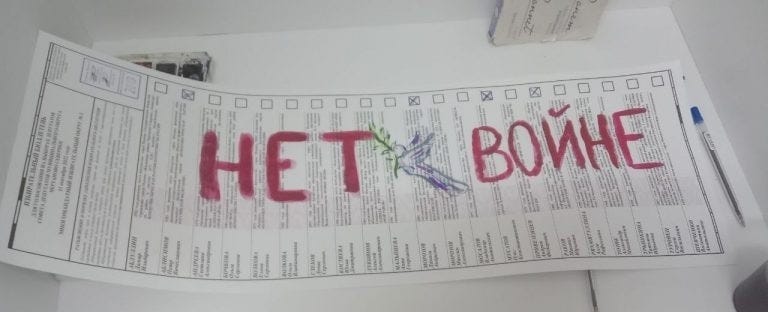

While we’re on the subject of exit and voice, Russia held “elections” last weekend, and it’s worth spending a few moments looking at the results. Unsurprisingly, there were no surprises: incumbents won, including the one non-United Russia candidate of note, Khakassia Governor Valentin Konovalov, who plays for the Communists; given the Communists’ demonstrative loyalty to the Kremlin, though, it’s hard to call that an opposition victory. The are-they-aren’t-they-opposition party Yabloko, which ran on a peace platform, was endorsed in numerous races by the Navalny team’s “Smart Voting” campaign and lost all of its head-to-head races but got a number of people into city councils, most prominently in Ekaterinburg and Novgorod. For profiles of some of Yabloko’s successful candidates, see this report from 7x7. Angelina Roshchupko had a fuller report on Yabloko’s successes and failures in Novaia Gazeta Europe, and Leonid Volkov reviewed the Smart Voting results from Ekaterinburg on his Telegram channel.

Most regions seem to have delivered results close to or above the 70/70 benchmark sent by the Kremlin for the upcoming presidential elections: 70% for the Kremlin’s preferred candidate, on 70% turnout. Statistical analysis, meanwhile, suggests varying degrees of falsification, but perhaps the biggest problem is officials’ handling of electronic voting data in Moscow to make forensic analysis basically impossible. For a full rundown of results, see Andrei Pertsev’s report in Meduza.

Sticking with politics and Andrei Pertsev, he had a report on Friday in Meduza on the proliferation of political youth camps modeled on the Seliger camp that Vladislav Surkov and the now defunct Kremlin youth group Nashi used to organize. As Pertsev writes, the Presidential Administration seems to be using these camps for three purposes: to build emotional commitment to the war, to identify “talent” for online influence campaigns, and, of course, to make money. Also on the ideological front, Anastasiia Snegova reports in Novaia Gazeta Europe on the increasing prevalence of preemptive censorship in the Russian cultural sector, with the Ministry of Culture and Presidential Administration becoming involved much earlier in the process than they used to. And Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan have a great article in Foreign Affairs on the growing role of the Russian Orthodox Church, as one of the few Russian institutions still able to project influence outside the country’s borders.

Most readers are likely to have seen Wednesday’s piece in New York Times, reporting that Russia was circumventing sanctions successfully enough to ramp up production of missiles and artillery shells, which set the war watchers abuzz, and for good reason. But it’s worth reading that article alongside two others: Daria Talanova’s data investigation in Novaia Gazeta Europe showing Russian arms manufacturers’ mounting difficulties in fulfilling orders, and Ekaterina Mereminskaia’s piece in iStories on Russia’s growing (and surprising) shortages of petrol and diesel. The best interpretation I’ve seen of these seemingly contradictory phenomena comes from the German economic analyst Janis Kluge, who wrote Friday in the Moscow Times on Russia’s resilience: yes, this war comes at a very real and a very high cost for Moscow, and particularly for the future of ordinary Russian citizens and the Russian economy as a whole, but thus far it has proved to be a cost the Kremlin is willing and able to bear.

Returning to the theme of dissatisfaction, Alexandra Prokopenko had an interesting piece in Carnegie Politika on Thursday, arguing that the Kremlin is creating enough new winners among the economic elite to maintain support for the war. (I tried to make a similar point a while back, as readers may remember, but Prokopenko does it better and more thoroughly.) The same day, though, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov lashed out at members of the elite who were trying to get out from under Western sanctions, calling them “traitors” lining up for their “12 pieces of silver” (perhaps suggesting they’re cheap, since Judas got 30). Make of that what you will.

And coming full circle to the question of Russia’s future, I’d highly recommend taking a look at two thought-provoking pieces: an interview in Novaia Gazeta Europe with political scientist Viacheslav Morozov on the challenge of overcoming Russia’s imperial past, and a dialogue between two CEPA fellows—Elena Davlikanova from Ukraine and Lyubov Sobol from Russia—on whether Russia can make the transition to democracy. There are no easy answers here, but that’s the point.

What I’m listening to

Another Durham band—the roots duo Viv & Riley—just released their new album, Imaginary People, and I’m regretting not having discovered them earlier. The music is reminiscent of the Civil Wars, though rougher around the edges. Like the Civil Wars, the songs are as heart-breaking as our present reality, and perhaps more beautiful than we deserve.

Thank you for your discussion of Hirschman's "exit, voice, loyalty" theory. It offers a reasonable explanation of the Russian public's quiescence to its government's war crimes and to their own diminished lives resulting from sanctions and Western opprobrium (no more vacations in Europe). Unfortunately, applying that theory to conditions in the US seems to reveal a similar quiescence but neither exit nor voice nor loyalty; many here just can't be bothered to even pay attention.

Another reason for quietly maintaining the status quo is personal benefit from the existing system, which is deeply and pervasiveness corrupt.

I was amused to see a brief item in a Daily Kos thread about the recent arrest of a Russian General for selling reserve military hardware and parts to paying customers outside Russia. (Some of the sold items were even rumored to find their way to Ukrainian fighters.)

If this sort of behaviour goes on at all levels, who is going to upset the apple cart?