In the opening scene of Fiddler on the Roof, a villager asks the rabbi, “Is there a proper blessing for the czar?”

“Of course,” replies the rabbi. “May G-d bless and keep the czar … far away from us.”

A few weeks ago, I started a Russian-language Telegram channel (and have been more than a little remiss in maintaining it) for the purposes of trying to have a bit more contact with people in Russia, given that I can’t travel there for the foreseeable future. I started by asking subscribers a number of questions about how their friends, neighbors, family members and colleagues were responding to various things going on in the country, and the phrase many of them kept returning to was, моя хата с краю—“my house is on the outskirts”.

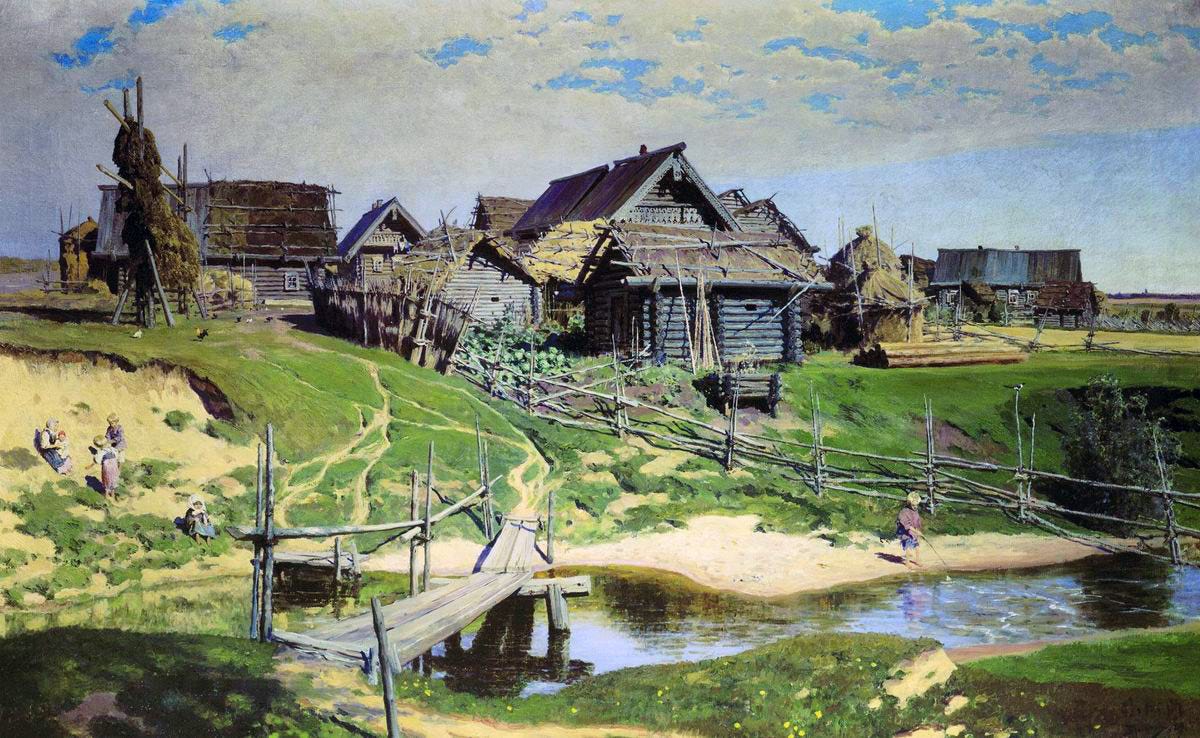

The phrase, which is shorthand for “I live my own life, what goes on in the community doesn’t concern me, leave me alone”, is problematic on at least a couple of levels. First, it’s essentializing, a way of condemning all Russians by means of some imagined cultural deficiency that they are all presumed to share. Second, most Russian villagers don’t live in хаты, they live in дома or избы or other dwellings; хаты are more commonly associated with Ukrainians, Poles and Belarusians, and so when the phrase is used derogatively (which is the only way it is ever used), it brings with it a heavy dose of chauvinism.

That’s part of the reason why I raised the scene from Fiddler, which will be familiar to most readers above a certain age—to show that the phenomenon is not peculiarly Russian. (And no, the Jews in Fiddler are not Russian. Happy to have that debate some other time and place.) Mostly, though, I raised it because it helps explain why the phenomenon is worth thinking about, my reservations notwithstanding. The residents of Anatevka want to keep the czar at bay not because they don’t care about what the czar does, but because when you live in a system of predatory power, caring too much is dangerous.

In other words, when we see people systematically disengage from politics, we need to ask why.

What I’m thinking about

In last week’s edition of the newsletter, I wrote about the idea of contingency, and how people dealing with large-scale uncertainty often find themselves guided less by the threats they actually face, than by the emotions that take hold in their social circles. I was, of course, writing mostly about how uncertainty was shaping Western analysis and policymaking. This week, I think it’s time to turn our sights back to Russia.

The stunning fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria—and thus the evident failure of a decade of Russian intervention—is, without a doubt, a momentous event. First and foremost, it will reshape the lives of some 23 million Syrians and millions more in the region. People who actually know something about Middle Eastern politics (i.e., not me) can explain what this will mean for politics and security more broadly. But the news this past week brought a certain amount of hyperventilating about the supposed effect on Russia itself, which doesn’t quite strike me as justified.

To wit, the Associated Press called Assad’s fall “a humbling blow” for Russia, the BBC termed it “a blow to Russia’s prestige”, and Sky News speculated that “Putin must be in crisis mode.” Writing in the New York Times, Hanna Notte opined that, “No amount of rhetorical gymnastics by Russia’s spin doctors can distract from the fact that the abandonment of Mr. al-Assad is the clearest sign, since Mr. Putin invaded Ukraine, that there are new limits on Russian power projection.” At CEPA, Ben Dubow wrote, “[Russia’s] security guarantees are increasingly seen as undeliverable, the sign of a country strong on rhetoric but weak in action.” To be clear, I have nothing but respect for all of the authors and venues involved, and I don’t think the analysis is wrong in its details. My beef is with the overall thrust that seems to have taken hold in punditworld.

Across these sources and others, Assad’s fall is argued to have punctured Putin’s carefully crafted image of consequence, with potentially catastrophic effects at home and abroad. Again, I’ll leave the Middle East question to the experts, but I found Nikolay Kozhanov’s analysis for Chatham House—suggesting that Moscow may be able to maintain most, if not all of its positions—convincing. Setting that aside, I’ll turn to the potential impacts within Russia itself.

The prospect that Putin’s failure in Syria could undermine his ability to maintain political power in Russia strikes me as dubious—not because it misreads the importance of Syria, but because it misunderstands the nature of Putin’s political power.

At its heart, the proposition that Putin might be weakened at home by the collapse of his intervention in Syria is of a kind with the proposition that he will have been weakened by the Prigozhin mutiny in the summer of 2023, or by the Wildberries incident this past summer, or the Ukrainian incursion into Kurskaya oblast. As Peter Pomerantsev argued in Foreign Affairs this October, each of these incidents and others like them risk exposing the fragility of the Kremlin’s control of the system it purports to govern, with potentially catastrophic effects for the confidence of both the masses and the elite in Putin’s ability to keep the show on the road. And that, as Tatyana Stanovaya argued also in Foreign Affairs, is why Prigozhin had to die. I frequently find myself agreeing with both Peter and Tatyana, and there is much in both of their pieces to like—but on this particular point, I’m going to have to disagree.

The problem I have with the argument about the importance of perceived competence is that it gets half of the contingency equation right, and half of it wrong. It is absolutely correct to say that a loss in perceived competence can trigger various constituencies to withdraw compliance from the regime. Indeed, that kind of dynamic is a big part of why the Soviet Union collapsed. And, as Sergei Guriev and Dan Treisman show in Spin Dictators, autocrats have good reason to try to convince their elites and masses that they are competent. But the operative word here is can, and to say that a loss in perceived competence can trigger a withdrawal of compliance doesn’t mean that it must.

The second half of the contingency equation involves the expectations that elites and masses place on those ruling them. In order for us to get from can to must, those expectations need to be strong. People need to believe that the competent functioning of the regime is critical to their livelihood, that a collapse of that competence will make them worse off, and/or that a restoration of competence could make them better off. Without that belief—without that sense of involvement and engagement with power—a collapse in confidence may sour the mood, but it will likely have little or no practical impact.

Putin’s saving grace has been and appears to remain the fact that most Russians—whether of the mass or elite variety—do not believe their lives and livelihoods to depend very much on what the regime does. For the masses, the state they have “enjoyed” throughout most if not all of living memory has oscillated between periods of being overtly predatory and merely neglectful, with long spells of outright dysfunction. That experience, in turn, has led to what the Russian sociologist calls “the inertia of passive adaptation”, and what I have called “aggressive immobility”; both concepts center on the desire “to keep the czar … far away from us.” Indeed, Levada Center data have shown for decades that ordinary Russians understand very well in whose interests Putin governs—and it isn’t them. (See the figure below.)

(It’s interesting, meanwhile, that the proportion of respondents who think that Putin serves the interests of ordinary citizens has gone up significantly since the war began, but that’s a topic for another day.)

This does not mean, however, that Russians see an inherently adversarial relationship with their state. As Graeme Robertson and I describe in Putin vs. the People (title notwithstanding), the persistent challenge for Russia’s liberal opposition has been not to convince voters that the Kremlin is corrupt and does not govern in the interest of the common citizen, but to convince them that any government could ever do any better. Most Russian citizens have accommodated themselves to this state of affairs, just as most people tolerate most of what they are asked to put up with on a daily basis, and do so willingly. The result, as I wrote in a 2017 article in Daedalus, is a “preparedness to see [the Russian state] as simultaneously dysfunctional and yet legitimate, unjust and yet worthy.”

A similar sensibility seems to extend to the elite. We’ve heard at various points since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that elites have been made to swallow their dissatisfaction in the name of loyalty and survival (see here, for example, and here). In fact, we’ve been hearing about elite dissatisfaction with Putin for at least a decade, and maybe more. Nevertheless, the elite have shown neither resistance nor defection nor even dissent on any noticeable scale. By definition, of course, living “on the outskirts” isn’t really an option for the elite, but does not appear to have stopped them from concluding that their political power need not be exercised beyond the scope of their narrow, individual material interests. They thus remain happy constituents of a system that increasingly constrains them but leaves them richer and less accountable than they have any right to be.

As a result, none of the shocks of the past few years—not the war itself, not sanctions, not mobilization, not Prigozhin, not Wildberries, not Kursk and other Ukrainian counter-attacks—have had any appreciable effect on mass or elite behavior. And that, in my view, is the key reason why I wouldn’t expect Syria or any other evidence of the Kremlin’s incompetence to have any political impact within Russia. Putin’s constituents are perfectly aware of the damage he has caused to the country, of his inability to manage its affairs effectively and in the common interest. Given everything they have seen in recent years, they cannot not be aware. If that stimulus elicits no response, it is because the Kremlin’s incompetence and indifference are, for most Russians, immaterial.

What I’m reading

I’m afraid I didn’t have much time to read this week, so it’s a short list. I promise to have more for you next week!

On Wednesday, Kholod published a monologue by a Russian in his late 50s who volunteered to go to war—on the Ukrainian side. “I decided to tell you about this damned war in detail,” he writes, “because I can see that many Europeans and even anti-war Russians think that the war will somehow end on its own. But that’s not going to happen.”

Also on Wednesday, Meduza published a primer on the ever-expanding definition of treason working its way through the Duma. Unsurprisingly, just about any professional interaction with foreigners could cause a severe vulnerability.

On Friday, Mediazona published a short profile of Alexei Gorinov, whose insistence on continuing to protest the war—even from the defendant’s cage of his trial—has become a viral object lesson in moral clarity and earned him an extra three years in prison. If you haven’t seen it, Meduza’s detailed report of his trial, from 29 November, is well worth a read.

Something I missed from a couple of weeks ago was an investigation by Proekt into a racket involving high-level Russian officials and private business interests (Proekt uses the term ‘oligarchs’, which I promised to avoid) to commit fraud on consumer goods markets. It’s an odd combination of ‘business as usual’ for the top of Russia’s political-economic food chain, and a sign of some desperation that they have to mine the spending of ordinary Russians to find their next billion.

What I’m listening to

Bear with me for a second, while I try to explain the series of leaps that got me to this week’s song.

The idea for featuring music in each issue of the newsletter comes from Paul Krugman, whose blog posts for the New York Times used to (and maybe still do) include music recommendations, as a way of reinserting some humanity into debates that often veered into the inhumane. This week brought Krugman’s last column in the Times, which got me thinking about that little piece of influence, and about how it was Krugman that first introduced me to the Civil Wars, a duet he once described as more sublime than contemporary society deserves.

Anyway, I was taken with the Civil Wars because I’m a sucker for a duet. (To wit, regular readers may have clocked my fondness for Shovels and Rope.) Anyway, this particular duet—while not new—is on regular rotation at home, and it’s been on my mind all week. I hope you like it as much as I do.

Reading your analysis, I was struck by how your conclusion about "aggressive immobility" might describe a plurality (majority?) of Americans' moods. Given the level of "perceived incompetence" many here attribute to the Biden administration and that Trump 2.0 is likely to foist upon us, I suspect that many here in America will adopt/have already adopted the Russian attitude that we too "live on the outskirts of town." Unless government has profound negative effects on our lives, we too believe that "caring too much is dangerous" - and futile - and decide that "our lives and livelihoods ...[do not] depend very much on what the regime does."

Another perspective on "aggressive immobility" .... In Candide, Voltaire's theme is often summarized as the words of a Turk sitting under a tree: "We must cultivate our garden" - frequently rephrased as "tend your garden." I'm thinking a lot of us Americans will follow that advice. https://www.openculture.com/2020/09/what-voltaire-meant-when-he-said-that-we-must-cultivate-our-garden.html

I, too, wondered whether all the op-eds/claims about Syria's affect on Putin were premature. I feel like the future of Syria has been predicted and explained in detail, merely a week after Assad fled. I guess it's how the 24-hour news cycle functions...but it's not helpful for the public's understanding.

Please do at some point cover the topic you mentioned, re: "the proportion of respondents who think that Putin serves the interests of ordinary citizens has gone up significantly since the war began." Thanks.